Viruses - sweetpotato

Contributors to this section: CIP, Lima, Peru (Carols Chuquillanqui, Segundo Fuentes, Ivan Manrique, Giovanna Muller, Willmer Pérez, Reinhard Simon, David Tay, Liliam Gutarra); CIP, Nairobi, Kenya (Ian Barker); FERA, UK (Derek Tomlinson, Julian Smith, David Galsworthy, James Woodhall).

|

Contents: |

Internal cork disease of sweetpotatoes

Scientific name

Sweet Potato Feathery Mottle Virus (SPFMV).

Significance

Some isolates of SPFMV cause economic losses (Campbell et al., 1974), especially in intolerant cultivars (Clark and Moyer, 1988).

In synergistic interaction with the crinivirus Sweet potato chlorotic stunt virus (SPCSV) causes the Sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD) which reduce yield of storage roots over 60%.

Symptoms

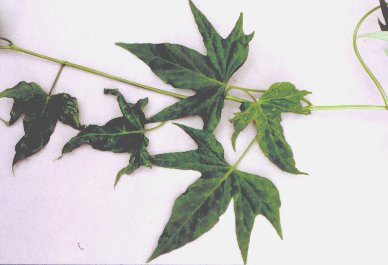

Foliage: Symptoms of SPFMV on leaves are often inconspicuous or absent. The classic irregular chlorotic patterns (feathering) along leaf veins and faint-to-distinct chlorotic spots with or without purple margins occur in some cultivars. Symptom visibility on foliage is influenced by cultivar susceptibility, degree of stress, growth stage, and strain virulence. Increased stress can lead to symptom expression, whereas rapid growth may result in symptom remission. Symptoms on storage roots depend on the strain of SPFMV and the sweetpotato variety (Clark and Moyer, 1988; CABI, 2007). The common strain causes no symptoms on storage roots of any variety, but the “russet crack” and “internal cork” strains cause external and internal dark necrotic lesions on certain varieties, respectively (Usugi et al., 1994; Clark and Moyer, 1988, CABI, 2007).

Hosts

Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) is the main natural host of SPFMV, although the virus occurs in wild Ipomoea species. The experimental host range of the virus is mainly restricted to the Convolvulaceae and Chenopodiaceae (CABI, 2007; Akel et al., 2009). Hewittia sublobata and Lepistemon owariensishan have been reported as new natural hosts of SPFMV (Tugume et al., 2008).

Geographic distribution

Worlwide (Clark and Moyer, 1988; Loebenstein et al., 2009), including Syria (Akel et al., 2009) and Italy (Parrella et al., 2006).

Biology and transmission

SPFMV is the most widespread virus infecting sweetpotato and possibly occurs wherever sweetpotato is grown (Brunt et al., 1990; Untiveros et al., 2008). SPFMV is transmitted from infected to healthy plants by aphids in the non-persistent manner (Clark and Moyer, 1988). Myzus persicae, Aphis gossypii, A. craccivora and Lipaphis erysimi, are the most important vector species. SPFMV is not seedborne. Seedlings and micropropagated plants are liable to carry the virus in trade and transport (CABI, 2007).

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- Two serotypes of Sweetpotato feathery mottle virus have been reported in Uganda (Karyeija, 2000).

- At CIP, the virus is detected by grafting on the indicator plant I. setosa and by serology (NCM-ELISA) with a broad spectrum antiserum. Its detection is also possible by RT-PCR.

Treatment/control

- In seed certification schemes, no virus infections must be tolerated during the growing season. Stocks of in vitro cultures used for propagation should be originated from pathogen-free plants and maintained under conditions designed to prevent infection and contamination.

Procedure followed at CIP in case of a positive test

- At CIP if the virus is detected the imported accession of germplasm must be cleaned by thermotherapy.

References and further reading

Akel E, Al- Chaabi S . 2009. New Natural Weed Hosts of Sweet potato Feathery Mottle Virus in Syria. Seventh Conference Of General Commission for Scientific Agricultural esearch Damascus, 3-4 August 2009. [online] Available from URl: http://www.gcsar.gov.sy/gcsaren/spip.php?article151 Date accessed 10 May 2010

Brunt A, Crabtree K, Gibbs A. (eds.). 1990. Viruses of tropical plants: Descriptions and lists from the VIDE database. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

CABI 2007. Crop Protection Compendium. [online] Available from URL: www.cabi.org/compendia/cpc/. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau International (CABI), Wallingford, UK. Date accessed 10 May 2010

Campbell RN, Hall DH, Mielines NM. 1974. Etiology of sweet potato russet crack disease, Phytopathology, 64:210–218.

Clark CA, Moyer JM. 1988. Compendium of sweetpotato diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. APS Press, Minnesota, USA. 74 p.

Loebenstein G, Thottappilly G, Fuentes S, Cohen J. 2009. Virus and Phytoplasma Diseases. pp. 105-134 Chapter 8 In: Loebenstein G, Thottappilly G. (eds.) The Sweetpotato. Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

Parrella G, De Stradis A, Giorgini M. 2006. Sweetpotato feathery mottle virus is the casual agent of Sweet Potato Virus Disease (SPVD) in Italy. BSPP New disease reports (Online). Volume 13: Feb 2006 to Jul 2006

Karyeija RF, Kreuze JF, Gibson RW, Valkonen JPT. 2000. Two serotypes of Sweetpotato feathery mottle virus in Uganda and their interaction with resistant Sweetpotato cultivars. Phytopathology 90 (11): 1250–1255

Untiveros M, Fuentes S, Kreuze J. 2008. Molecular variability of sweet potato feathery mottle virus and other potyviruses infecting sweet potato in Peru. Archives of virology: 153(3):473–83.

Tugume AK, Mukasa SB, Valkonen JP. 2008. Natural Wild Hosts of Sweet potato feathery mottle virus Show Spatial Differences in Virus Incidence and Virus-Like Diseases in Uganda. Phytopathology 98(6):640–52

Usugi T, Nakano M, Onuki M, Maoka T, Hayashi T. 1994. A new strain of sweetpotato feathery mottle virus that cause russet crack on fleshy roots of some Japanese cultivars of sweetpotato. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Japan 60: 545–554.

Seed Health General Publication Published by the Center or CGIAR

Moyer JW, Jackson GVH, Frison EA. (eds.). 1989. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Sweet Potato Germplasm. Food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome/International Board for Plant Genetic Resources, Rome.

SPFMV - symptom in SP4 (photo: CIP) |

SPFMV - symptom in SP5 (photo: CIP) |

Scientific name

Sweet Potato Mild Mottle Virus (SPMMV)

Significance

No data available.

Symptoms

SPMMV was isolated in East Africa from sweetpotatoes exhibiting leaf mottling, veinal chlorosis, dwarfing, and general stunting of the plants. Symptoms can vary according to cultivars’ resistance and can be less severe or even symptomless in tolerant genotypes; some cultivars are apparently immune (Hollings et al. 1976 a, b; Jansson et al., 1991). SPMMV occurs in sweetpotatoes together with other viruses and produced symptoms more severe (Aritua and Adipala, 2006; Hoyer et al., 1996).

Hosts

SPMMV (photo: CIP) |

The only known natural host of SPMMV is Ipomoea batatas, but the virus is experimentally transmissible by mechanical inoculation to at least 45 species in 14 plant families (Clark and Moyer, 1988).

Geographic distribution

Asia, Africa, Oceania, South America (no confirmed).

Biology and transmission

SPMMV is transmitted by whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci), probably in the persistent manner (Hollings et al., 1976 a, b. Valverde et al., 2004). The virus is not seedborne (Hollings et al., 1976 a, b). Seedlings and micropropagated plants are liable to carry the pest in trade and transport (CABI, 2007).

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At CIP, the virus is detected by grafting on the indicator plant I. setosa and by serology (NCM-ELISA).

Treatment/control

- In seed certification schemes, no virus infections must be tolerated during the growing season. Stocks of in vitro cultures used for propagation should be from pathogen-free plants and maintained under conditions designed to prevent infection and contamination.

Procedure followed at CIP in case of a positive test

- At CIP if the virus is detected the imported germplasm must be cleaned by thermotherapy.

References and further reading

Aritua V, Adipala E. 2006. Characteristics and diversity in sweetpotato-infecting viruses in Africa. Proceedings of the 2nd international symposium on sweetpotato and cassava: Innovative technologies for commercialization. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, June 14–17, 2005 ).

CABI 2007. Crop Protection Compendium. [online] Available from URL: www.cabi.org/compendia/cpc/. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau International (CABI), Wallingford, UK. Date accessed 10 May 2010

Clark CA, Moyer JW. 1988. Compendium of sweetpotato diseases. The American Phytopathological Society, ST Paul, MN, USA. 74 p.

Hollings M, Stone OM, Bock KR.1976a. Purification and properties of sweet potato mild mottle, a whitefly-borne virus from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) in East Africa. Annals of Applied Biology, 82(3):511–528.

Hollings M, Stone OM, Bock KR.1976b. Sweet potato mild mottle virus. CMI/AAB Descriptions of Plant Viruses No. 162. Wellesbourne, UK: Association of Applied Biologists.

Hoyer U, Maiss E, Jelkmann W, Lesemann DE, Vetten HJ. 1996. Identification of the coat protein gene of a sweet potato sunken vein closterovirus isolate from Kenya and evidence for a serological relationship among geographically diverse closterovirus isolates from sweet potato. Phytopathology, 86(7):744–750.

Jansson R, Raman KV. 1991. Sweet Potato Pest Management, A Global Perspective. Westview Press Inc. Colorado, USA. 458 p.

Valverde RA, Sim J, Pongtharin L. 2004. Whitefly transmission of sweet potato viruses. Virus Research 100 (1): 123–128.

Seed Health General Publication Published by the Center or CGIAR

Moyer JW, Jackson GVH, Frison EA. (eds.). 1989. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Sweet Potato Germplasm. Food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome/International Board for Plant Genetic Resources, Rome.

Scientific name

Sweet Potato Latent Virus (SPLV)

Significance

No data available.

Symptoms

SPLV may cause mild chlorosis but in most cultivars the infection is symptomless. Symptoms often disappear after infection, but the plants remain infected (Loebenstein and Thottappily, 2003).

Hosts

Ipomoea batatas is the natural hosts.

Geographic distribution

Asia, Africa.

Biology and transmission

The virus can be transmitted by aphids, by mechanical inoculation, and by grafting. SPLV is not a seedborne virus (Loebenstein and Thottappily, 2003).

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At CIP, the virus is detected by grafting on the indicator plant I.setosa and by serology (NCM-ELISA).

Treatment/control

- In seed certification schemes, no virus infections must be tolerated during the growing season. Stocks of in vitro cultures used for propagation should be from pathogen-free plants and maintained under conditions designed to prevent infection and contamination.

Procedure followed at CIP in case of a positive test

- At CIP if the virus is detected the imported germplasm must be cleaned by thermotherapy.

References and further reading

Clark CA, Moyer JW. 1988. Compendium of sweetpotato diseases. The American Phytopathological Society, ST Paul, MN, USA. 74 p.

Domola MJ, Thompson GJ, Aveling TAS, Laurie SM, Strydom H, van Den Berg AA. 2008. Sweet potato viruses in South Africa and the effect of viral infection on storage root yield. African Plant protection 14: 15–23

Feng G, Yifu G, Pinbo Z. 2000. Production and deployment of virus-free sweetpotato in China. Crop Protection 19 (2) : 105–111

Green SK, Kuo YJ, Lee DR. 1988. Uneven distribution of two potyviruses (feathery mottle virus and sweet potato latent virus) in sweet potato plants and its implication on virus indexing of meristem derived plants International Journal of Pest Management 34(3): 298–302

Loebenstein G, Thottappily G. (eds.). 2003. Viruses and Virus-Like Diseases of Major Crops in Developing Countries. Dortrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 840 pp

Njeru RW, Bagabe MC, Nkezabahizi D, Kayiranga D, Kajuga J, Butare L, Ndirigue J. 2008. Viruses infecting sweet potato in Rwanda: occurrence and distribution. Annals of Applied Biology 153 (2):215–221.

Susuki T, Ohkoshi K, Sakai J, Hanada K.1999. Sweetpotato Latent Virus Detected from Sweetpotato in Chinba Prefecture. Annals of the Phytopathological Society of Japan 65(3):380

Yun WS, Lee YH, Kim KH. 2002. First report of Sweet Potato latent virus and Sweet potato chlorotic stunt virus isolated from sweet potato in Korea. Plant Pathol. J. 18(3): 126–129

Seed Health General Publication Published by the Center or CGIAR

Moyer JW, Jackson GVH, Frison EA. (eds.). 1989. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Sweet Potato Germplasm. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome/International Board for Plant Genetic Resources, Rome.

Scientific name

Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV)

Significance

CMV has the widest host range of any virus and is one of the most damaging viruses of temperate agricultural crops worldwide (Gallitelli, 2000).

Symptoms

CMV causes stunting, chlorosis and yellowing of plants (Cohen et al., 1988; Cohen and Loebenstein, 1991) when interacting with SPCSV.

Hosts

CMV has a wide host range and infects more than 800 species of both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants from over 85 families (Kaper and Waterworth, 1981; Palukaitis et al., 1992). CMV has been isolated from I. setifera (Migliori et al., 1978).

Sweetpotatoes can easily be infected by CMV if the plant is already carrying the whitefly-transmitted SPCSV (Cohen and Loebenstein, 1991).

Geographic distribution

Asia, Africa, Europe, North America, Central America, South America, Oceania (CABI, 2007). CMV has been reported in sweetpotato so far only from Israel, Uganda, Kenya, Japan, South Africa, New Zealand, and Egypt (Loebenstein and Thottappily, 2003).

Biology and transmission

CMV is disseminated by vegetative propagation. Mechanical transmission of CMV to healthy sweetpotato plants failed in different assays. It is also non-persistently transmitted by a large number of aphid species. CMV can infected sweetpotato when transmitted by grafting (Untiveros et al. , 2007).

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At CIP, the virus is detected by grafting on the indicator plant I. setosa and by serology (NCM-ELISA).

Treatment/control

- In seed certification schemes, no virus infections must be tolerated during the growing season. Stocks of in vitro cultures used for propagation should be from pathogen-free plants and maintained under conditions designed to prevent infection and contamination.

Procedure followed at CIP in case of a positive test

- At CIP if the virus is detected the imported germplasm must be cleaned by thermotherapy.

References and further reading

CABI 2007. Crop Protection Compendium. [online] Available from URL: www.cabi.org/compendia/cpc/. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau International (CABI), Wallingford, UK. Date accessed 10 May 2010

Cohen J, Loebenstein G. 1991. Role of a whitefly-transmitted agent in infection of sweet potato by cucumber mosaic virus. Plant Dis. 75:291-292.

Cohen J, Loebenstein G, Spiegel S. 1988. Infection of sweet potato by cucumber mosaic virus depends on the presence of sweet potato feathery mottle virus. Plant disease 72:583–585

Gallitelli D. 2000. The ecology of cucumber mosaic virus and sustainable agriculture. Virus Research, 71: 9–21.

Kaper JM, Waterworth HE. 1981. Cucumoviruses. In: Kurstak E. (ed.). Handbook of Plant Virus Infections and Comparative Diagnosis. Amsterdam, North Holland: Elsevier, 257–332.

Loebenstein G, Thottappily G. (eds.). 2003. Viruses and Virus-Like Diseases of Major Crops in Developing Countries. Dortrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 422-496.

Loebenstein G, Fuentes S, Cohen J, Salazar. 2003. Sweetpotato. pp. 223–248 In: Virus and Virus-like Diseases of Major Crops in Developing Countries. Loebenstein G,Thottappilly G. (eds). Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Migliori A, Marchoux G, Quiot JB. 1978. Dynamique des populations du virus de la mosaique du cocombre en Guadeloupe. Ann. Phytopathol. 10:455–466.

Palukaitis P, Roossinck MJ, Dietzgen RG, Francki RBI.1992. Cucumber mosaic virus. Advances in Virus Research 41:281–348.

Untiveros M, Fuentes S, Salazar LF. 2007. Synergistic interaction of Sweet potato chlorotic stunt virus (Crinivirus) with carla-, cucumo-, ipomo- and potyviruses infecting sweet potato. Plant Dis. 91: 669-676.

Seed Health General Publication Published by the Center or CGIAR

Moyer JW, Jackson GVH, Frison EA. (eds.). 1989. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Sweet Potato Germplasm. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome/International Board for Plant Genetic Resources, Rome.

Comments

- No comments found

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest