CGKB News and events Procedures

Please click on the boxes in the diagram below or use the menu on the left to go to the topic of your interest.

Chapter 17: Plant health and germplasm collectors

R. Macfarlane

Whitby Porirua, New Zealand

E-mail:bob.macfarlane(at)maf.govt.nz

G. V. H. Jackson

Queens Park Sydney, Australia

E-mail: gjackson(at)zip.com.au

E. A. Frison

Bioversity International, Rome, Italy

E-mail: e.frison(at)cgiar.org

|

2011 version |

1995 version |

||

|

Open the full chapter in PDF format by clicking on the icon above. |

|||

This chapter is a synthesis of new knowledge, procedures, best practices and references for collecting plant diversity since the publication of the 1995 volume Collecting Plant Genetic Diversity: Technical Guidelines, edited by Luigi Guarino, V. Ramanatha Rao and Robert Reid, and published by CAB International on behalf of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) (now Bioversity International), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The original text for Chapter 17: Plant Health and Germplasm Collectors, authored by E. A. Frison and G. V. H. Jackson has been made available online courtesy of CABI. The 2011 update of the Technical Guidelines, edited by L. Guarino, V. Ramanatha Rao and E. Goldberg, has been made available courtesy of Bioversity International.

Please send any comments on this chapter using the Comments feature at the bottom of this page. If you wish to contribute new content or references on the subject please do so here.

Back to list of chapters on collecting

Internet resources for this chapter

Abstract

When plant germplasm is moved nationally or internationally, there is a risk of the concomitant movement of pests (insects, pathogens, weeds and other organisms). Further, the quality of samples may be compromised by pests affecting viability during storage or, later, during multiplication and characterization.

This chapter suggests what collectors need to do to minimize these dangers. It is divided into (1) what to do when planning collecting missions (assembling the pest information, plant-health documents, intermediate quarantine, pest identification), (2) what to do in the field (minimizing the pest risk, record keeping, preservation of pest specimens), and finally, (3) what to do back at the base (preparing samples for inspection, phytosanitary treatments and certification, documents, and preparation of pests for identification). If followed systematically, these guidelines will facilitate plant germplasm reaching its destination unhindered, and will contribute to its value.

Introduction: the need for healthy germplasm

Uncontrolled movement of plant germplasm between countries spreads pests, but regulation of the movement of plant germplasm can help to reduce these risks. Pests, as defined by the International Plant Protection Convention (lPPC) (https://www.ippc.int/index.php?id=1110589&L=0), are “any species, strain or biotype of plant, animal or pathogenic agent injurious to plants or plant products” (IPPC 2010). (The IPPC facilitates cooperation between contracting parties to protect the world's cultivated and natural plant resources from the spread and introduction of pests of plants, while minimizing interference with the international movement of goods and people.)There are those that can be easily seen with the naked eye, such as insects, mites, slugs and snails, rats, plants and seeds, and those that are microscopic, such as fungi and the like, bacteria, phytoplasma, viruses and viroids. Previously, pests were considered to be only those organisms potentially damaging to crops, but now the term pest also includes newly introduced organisms that might damage ecosystems and plant and animal biodiversity.

Because there are dangers inherent in the movement of plant germplasm, most countries have legislation to regulate the entry (and sometimes the internal movement) of plants, plant parts and their products. In particular, the movement of wild collected germplasm causes significant concern, as its pest status is likely to be poorly known. Consignments of germplasm arriving in the importing country without proper documentation will be treated, reshipped or destroyed, irrespective of their botanical significance, the type of pest infestation or the status of the collector. To reduce the risk of accidental transfer of pests, germplasm should always be collected, processed and shipped in compliance with the phytosanitary requirements of the importing country. Contact details of most countries’ plant quarantine services can be found on the IPPC website.

It is possible, from long experience and sheer weight of knowledge of a plant species, that collectors might be better informed about the possible presence of quarantine pests associated with plant germplasm than the authorities in the importing country. In such cases, they should divulge this information, while at the same time ensuring that the germplasm collected and dispatched is free of pests to the extent that is possible.

There are other, perhaps less obvious, reasons why pests should be given attention when germplasm is collected. Pests might affect the quality, and therefore the usefulness, of germplasm samples. Infection by pathogens can reduce the viability of seeds during storage. When material is multiplied, growth may be distorted, colours altered and disease susceptibility increased. These changes may make it difficult, if not impossible, to collect characterization and preliminary evaluation data, and some important characteristics, crucial for plant-improvement schemes, might go undetected. In addition, infested samples are unlikely to be distributed. They cannot be grown out and regenerated and, if stored, they will remain unused and will deteriorate.

It is, therefore, important to know what pests are likely to be associated with the target gene pool. This will allow an assessment of the risks associated with moving the germplasm, as well as providing for appropriate measures to be devised to reduce the risk to a minimum. It is also important to document any pests present on the target species at the time of collecting. This information, part of the passport data of the sample, will improve the usefulness of the germplasm and will also help during quarantine examination.

For all these reasons, it is often useful to include a plant-protection specialist in collecting teams if funds and logistical considerations allow. Preferably, this should be a plant pathologist experienced in the species to be collected, as pathogens are more difficult than insects and mites to detect during collecting and to eradicate from plant samples. If a plant-protection specialist cannot participate in the collecting mission, collectors should become familiar with the major pests of the target species. In all cases, collectors will have to ensure that the phytosanitary requirements of the importing country have been met and proper documentation has been assembled so that plant samples reach their intended destination unhindered.

This chapter gives guidelines on how these issues may be addressed. It considers what must be done at the planning stage, while collecting in the field and, finally, just before samples are dispatched.

Planning the collecting mission

At the planning stage, attention must be given to the pests that might be encountered on the target species, and to the importing country’s regulations governing plant movement. The following questions need to be considered when assembling information on plant pests:

-

What pests have been recorded on the target species in the country of collecting, especially in the target area?

-

What plant parts are they found on?

-

How are the pests transmitted?

The following questions need to be answered to ensure compliance with phytosanitary regulations:

-

What is the final destination(s) of all samples, including subsamples?

-

What are the phytosanitary import requirements of the country(ies) of destination?

-

What are the procedures for obtaining a phytosanitary certificate in the country of collecting?

-

What are the procedures for verifying that the phytosanitary requirements of the importing country have been met prior to export?

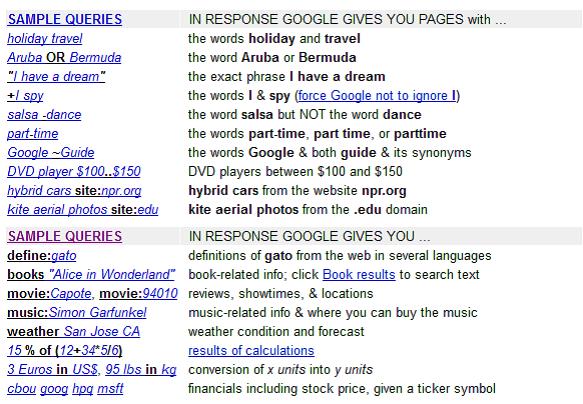

Assembling information on pests

Since the first edition of this document was published, there has been an enormous change in the availability of information on plants and other organisms. The internet now allows immediate access to the most up-to-date information available in publications, research centres and museums worldwide. Perhaps the first point of contact for a collector seeking information on a plant or pest is to run a search for a pest under its presently accepted name (and at least one of its synonyms) through a search engine such as Google, Bing or Yahoo. This will generally turn up several significant leads for further enquiry, often with researchers familiar with the species being searched.

There are now literally hundreds of databases publicly available over the internet, and many others with restricted access for either commercial or confidentiality reasons. A selection of these is provided in the reference section, below, along with a selection of texts that may be consulted for information on the pests of specific crops. For example, the American Phytopathological Society publishes a particularly useful set of documents on the identification of crop plant diseases (www.cplbookshop.com/glossary/G583.htm).

On pest distributions, the following are important sources for accurate data on the worldwide distribution of plant pests and diseases of economic or quarantine importance:

|

Distribution maps of pests |

lIE (1968 et seqq.) |

|

|

Distribution maps of plant diseases |

IMI (1942 et seqq.) |

Collectors should confirm with the relevant institutes that these maps contain the most up-to-date information. Detailed descriptions, including notes on the transmission of many of the pests figured in the maps, can be sought from the following publications:

|

Descriptions of fungi and bacteria |

IMI (1964 et seqq.) |

|

|

Descriptions of plant-parasitic nematodes |

lIP (1972 et seqq.) |

|

|

Descriptions of plant viruses |

CMIIAAB (1970-1984) AAB (1985 et seqq.) |

The CABI Crop Protection Compendium (CPC) (www.cabi.org/cpc) is also a useful source of information on some 3000 pests, diseases, natural enemies and crops (with 400 recently commissioned sheets added in 2010) and basic information on 27,000 more species. The CPC helps with pest identification and distribution (including maps) and with phytosanitary and quarantine issues.

On viruses, CABI and the Australian National University have collaborated on a major database: the Virus Identification Data Exchange (VIDE). Viruses of Tropical Plants (Brunt et al. 1990) is an output of the database, as is Plant Viruses Online: Descriptions and Lists from the VIDE Database (Brunt et al. 1996). This site also provides links to some excellent web sites on plant viruses.

The Consultative Group on International Agriculture Research (CGIAR) supports a consortium of research centres around the world, many of which focus on specific crop plants:

-

Africa Rice Center

-

Bioversity International

-

International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT)

-

Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR)

-

International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT)

-

International Potato Center (CIP)

-

International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA)

-

International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT)

-

International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA)

-

International Rice Research Institute (IRRI)

-

World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF)

Many of these research centres publish useful illustrated guides to the pests of their mandate crops. These are particularly useful in the field.

The CGIAR also has an online portal, the Crop Genebank Knowledge Base (http://cropgenebank.sgrp.cgiar.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=137&Itemid=238&lang=english), with guidelines for the safe transfer of germplasm for 15 seed crops and five clonally propagated crops under the mandate of CGIAR germplasm banks. In the introduction, the website states that it “summarizes information on current practices and guidelines for the safe transfer of germplasm gathered from the seed and crop health laboratories from CGIAR Centres in charge of the different crops”.

For each of the crops of interest there are sections on (1) germplasm import and export requirements, (2) technical guidelines for the detection and treatment of pests and pathogens and the safe transfer of germplasm and (3) best practices in place at the CGIAR Centres.

In addition, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and Bioversity International have published a series of booklets of crop-specific technical guidelines for the safe movement of germplasm (published under Bioversity’s previous names: International Board of Plant Genetic Resources and International Plant Genetic Resources Institute). They describe technical procedures that minimize the risk of introducing pests with the movement of germplasm for research, crop improvement, plant breeding, exploration or conservation. The recommendations in these guidelines are intended for germplasm for research, conservation and basic plant breeding programmes; they are not meant for trade and commercial consignments concerning the export and import of germplasm. Each booklet is divided into two parts: the first makes recommendations on how best to move the germplasm of the crop concerned and lists institutions recovering and/or maintaining healthy germplasm, the second covers the pests and diseases of quarantine concern, giving a description of therapy and indexing methodologies. So far, guidelines have been produced for the following crops (full citations and URLs are provided in the reference section below):

|

Acacia spp. |

Musa spp. |

There are many older texts that have crop-by-crop analysis of the problems and risks attendant on the transfer of plant germplasm, such as Hewitt and Chiarappa (1977), and these, too, can often contain information that remains useful.

Finally, pest surveys might also be consulted, if available, to determine which pests have been recorded on the target species in the collecting region. However, in many countries, such surveys are far from complete: sometimes, they have not been done at all, are outdated or do not cover the entire country, concentrating on the more easily accessible areas. Another problem is that pest surveys tend to record pests of crop plants, neglecting wild relatives, and rarely include native plants. This lack of information is a major barrier to the formulation of quarantine regulations appropriate to the exchange of germplasm of many plant species, including crop species.

Assembling the required plant health documents

It is essential to begin making phytosanitary arrangements early in the planning phase of any collecting expedition. Delays in obtaining the appropriate documents are common, but without these documents, the mission might have to be postponed or, worse, the samples destroyed. It is the responsibility of collectors to obtain the necessary documents in order to transfer plant germplasm. Two documents are commonly required for international plant transfer: an import permit and a phytosanitary certificate.

The import permit

The import permit must be obtained from the country or countries of destination of the germplasm well before the mission sets out. Information is also needed on how to obtain a phytosanitary certificate in the country of collecting and whether other authorizations are required to export germplasm, such as authorization under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which is an international agreement between governments that aims to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of these species. The FAO/IPPC Secretariat has a list of plant-protection services worldwide with contact addresses of the authorities responsible for issuing these documents. This list is available online at https://www.ippc.int/index.php?id=1110520&no_cache=1&type=contactpoints&L=0.

Regulations differ among countries according to the perceived risks involved in making the importation; the conditions of entry will be detailed on the import permit. Treatments may be required both in the country of export and in the country of import. If sub-samples are to be sent to several countries, permits must be obtained from each one. When no conditions apply and germplasm is allowed unconditional entry, it is advisable to obtain a document from the plant-protection service of the importing country to that effect. This will facilitate inspections at the border.

Usually, two copies of the import permit are provided. The top copy should accompany the consignment (if there is to be only one) and the other copy should be retained by the collector. A photocopy is usually allowed for multiple consignments.

It is recommended that collectors advise the importing phytosanitary border authorities of the number and approximate size of samples well ahead of arrival, so that the quarantine inspection service can plan to process the samples quickly. If the plants are to be grown in post-entry quarantine in the importing country or in a third country, then arrangements for this must be made during the planning phase of any expedition to ensure that facilities and space are available when needed.

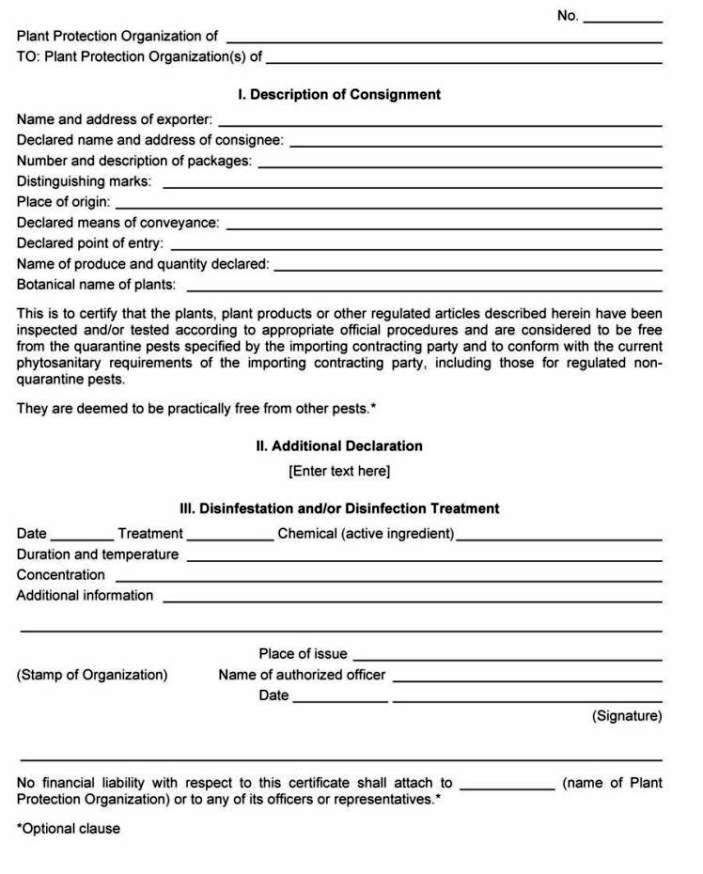

The phytosanitary certificate

The phytosanitary certificate is issued by the quarantine authority of the exporting country, certifying that the product meets the phytosanitary regulations of the importing country. Consignments are inspected and the certificate issued if they are “free from quarantine pests and practically free of injurious pests” (see the IPPC model phytosanitary certificate, appendix 17.1 at the end of this chapter). A “quarantine pest” is different from a merely “injurious pest” in this statement in that it is of potential national economic importance to the country and not yet present there, or present but not widely distributed, and being actively controlled (IPPC 2010).

In some instances, in order to reduce the overall pest risk, germplasm consignments will need to be given phytosanitary treatments in the country of origin (see chapter 20 on the potential risks for seed viability of such treatments). Fumigation may be requested or the samples may be dipped or dusted in an insecticide or fungicide, given a hot-water treatment, or whatever is considered appropriate by the importing country. The treatments should be applied exactly as requested. If the collector is not confident that a treatment will be applied correctly in the exporting country and that it might fail to control the pest or that the germplasm might be damaged, it may be possible to negotiate with the importing country to have the treatment done under secure quarantine after arrival there. The permit may seek “additional declarations” verifying that these treatments have been applied as required. These, as well as details of the treatments, must be specified/declared on the phytosanitary certificate. Finally, the certificate should be signed by the authorized government representative.

Under no circumstances should alternative treatments to those specified on the import permit be applied without first requesting the authority of the importing country. Alternative treatments may be ignored by the importing quarantine inspector and a second treatment applied, which could reduce the viability of the germplasm. Likewise, if no treatments are requested, none should be given, since importing countries may wish to inspect or test germplasm consignments, and treatments already applied to seeds, for instance, may mask symptoms of seed-borne pathogens and interfere with laboratory tests. If seeds are treated prior to entry, contrary to the conditions of the permit, this could seriously jeopardize their importation.

Where germplasm samples are to be sent to more than one country, it is necessary to obtain phytosanitary certificates that comply with the requirements of each destination. It is important that the certificate(s) should be issued without amendment or erasure. Many countries refuse to accept altered certificates.

A fee may be charged for fumigation or disinfection treatments and, occasionally, for inspection.

Two copies of the phytosanitary certificate should be obtained, if possible. If there is only one, then the collector should make a copy. The original phytosanitary certificate should accompany the consignment and the copy should be kept with the other records of the collecting mission.

Documentation and intermediate quarantine

Collectors are responsible for arranging the documentation for germplasm samples that have to be grown in intermediate (third-country) quarantine. Such arrangements are necessary when it is unsafe to make transfers directly to the importing country. Procedures are essentially similar to those outlined above: an import permit must be obtained from the quarantine authority of the intermediate country. A copy of this should accompany the consignment, together with the phytosanitary certificate showing any treatments or endorsements requested on the permit. After the samples have been grown in intermediate quarantine and declared safe for further transfer, an import permit must be obtained from the country of final destination and a new phytosanitary certificate issued by the intermediate country.

Planning the identification of pests

Misidentifications of pests can seriously jeopardize the usefulness of consignments. Identification services for fungi, bacteria, nematodes are provided by CABI Global Plant Clinic (www.cabi.org/default.aspx?site=170&page=1017&pid=2301).

Costs vary depending on whether or not a country is a member of CABI. CABI also publishes useful directories of organizations, such as the International Mycological Directory (Hall and Hawksworth, 1990). It may be possible to arrange with the Danish Government Institute of Seed Pathology for Developing Countries (in Hellerup, Denmark) for the identification of important seed-borne diseases of tropical countries.

Identification of virus and virus-like infections is more problematical. Specimens need to be sent to institutes specializing in particular crop plants. Lists of institutes providing this service (such as the Tropical Virus Unit at the Institute of Arable Crops Research, Rothamsted Experimental Station, UK) can be found in the appropriate booklet in the FAO/IPGRI series of safe transfer guidelines. CABI also gives advice.

Identification of arthropods and many other biota can be obtained at a cost through the Natural History Museum, South Kensington, UK (www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/contact-enquiries/identification-and-general-science-enquiries/index.html), and many other museums. In all cases, arrangements must be made well ahead of dispatch to allow the orderly processing of specimens. Import permits may be needed. If so, these must be obtained from the appropriate authorities in the country where specimens are to be examined. Collectors should ensure that the institutes making the identifications know where to send the results.

In the field

Minimizing the pest risk

Familiarity with the symptoms caused by pests and with which plant parts are most likely to be contaminated by the pests of concern is essential. In general, the risk of spreading pests with germplasm is greatest if rooted plants are moved. This is because of the likelihood that nematodes and other soil-borne pathogens will be present; these are difficult to treat without destroying the plant tissues. Other types of vegetative propagating material (e.g., stems, bulbs, corms, etc.) also present a risk, mainly because of infection from systemic pathogens. The international movement of seeds and pollen is considered safer, as fewer pests are harboured by these plant organs. Phytosanitary considerations may therefore contribute to the decision as to what plant part(s) to collect.

It may be possible to apply curative treatments to lessen or eradicate the pest risk. For surface-borne pathogens and insects, pesticide treatments and fumigation may be tried. Where virus, virus-like organisms and internally borne fungi and bacteria are a threat, thermotherapy and shoot-tip culture are most appropriate.

For vegetatively propagated species, transfer of germplasm as in vitro cultures will greatly reduce the pest risk. Nevertheless, it should be stressed that in vitro cultures do not eliminate the risk entirely. They should be complemented by indexing (testing) for viruses and virus-like organisms that are likely to be present in the area where the germplasm was collected.

The technical guidelines for the safe transfer of germplasm give general advice to collectors on the type of germplasm considered safe to move internationally, as well as detailed technical recommendations on how the germplasm may be treated to ensure that it is free of pests. In some instances, because of the severity of the pest and the difficulty of collecting healthy material from the field, the guidelines advise on transfer of material through a third country, where therapy and indexing procedures can be carried out to ensure freedom from internally borne pathogens. The general recommendations of the guidelines are useful even for crops not specifically covered in the series to date.

Recording data on pests

It is important for collectors to record the pests present on their target species and to note whether other pests are present in the target region. Noting that plants are free of pests in an area where pests are common is equally important. Collectors should attempt to describe the symptoms caused by pests. It is, however, often difficult for someone untrained in plant pathology or entomology to do this. Symptoms may be caused by a combination of several pests, or the causal agent may be obscured by the presence of a minor one or by an opportunistic saprophyte. Symptoms due to root attack or internal pathogens are often particularly difficult to interpret. Where there is doubt as to the identification of pests, plant specimens showing typical symptoms should be collected and dried or preserved by other means, as appropriate (see below).

A description of symptoms should include information on the following (Sonoda 1979):

-

the general condition of the plant

-

the plant part(s) affected

-

the type of damage

-

the stage of growth affected

Rating the severity of attack, both in terms of its effect on the individual plant(s) affected and in terms of the percentage of the population affected, will increase the value of the information. Descriptor lists are published by Bioversity International for many crops, cataloguing the important pests and giving scales of severity. These are available online at www.bioversityinternational.org/research/conservation/sharing_information/descriptor_lists.html.

Colour photographs showing the full range of symptoms, including close-ups of damaged areas and of the pests themselves, are often useful diagnostic tools (Sonoda 1979).

Farmers' knowledge of pests can be extensive and detailed. Some examples are given by Altieri (1993). Collectors can often complement the kinds of observations described above with discussions with knowledgeable local people.

Preservation of pests associated with germplasm samples

Correct identification of pests depends on the quality of the specimens prepared in the field. Collectors should be equipped at least with specimen bottles, alcohol (75% isopropyl alcohol) and formalin for preserving insects, mites and nematodes, and with newspapers and plant presses for making dried herbarium specimens of plants with fungal and bacterial diseases (chapter 27). Specimens may need to be shared among several institutes, and sufficient material should be collected to allow this.

Sonoda (1979) gives guidelines on capturing, killing and storing insects and other pests in the context of germplasm collecting. For insect pests, representative specimens of all life stages may be necessary for taxonomic identification. Insects can be captured using nets, by beating plants over a cloth or by using an aspirator. They can be killed using potassium cyanide or ethyl acetate, both of which are dangerous and should be clearly labelled and stored properly. Some insects must be pinned (e.g., beetles, flies and wasps); others can be stored in alcohol (e.g., caterpillars and other larvae, ants, aphids, scales and mealybugs) and others can be stored in small envelopes (e.g., moths and butterflies).

Dried specimens of diseased plants should include as much of the plant as possible, showing both old and new lesions. Fresh specimens can also be collected and stored in plastic bags. They will remain useful longer if refrigerated. Fungal and bacterial pathogens may be isolated from diseased plants in the field, but this requires sterile techniques and is not often feasible in the context of plant germplasm collecting.

Plants infected with viruses or virus-like organisms present the collector with the greatest challenge, as the material needs to be processed in different ways according to the type of pathogen. Where tissues are thought to contain non-cultivable mollicutes (formerly referred to as mycoplasma-like organisms), they need to be fixed in glutaraldehyde; whereas, tissues for virus examination may be sent fresh, dried as thin (1mm x 10mm) sections over calcium chloride (or silica gel) or as sap stained on electron microscope grids. Because of the complexity of the subject, it is essential that, prior to departure, collectors seek advice on the preservation of specimens from the institutes where the specimens are to be sent for examination.

Details of methods of preserving various kinds of diseased material can be found in The Plant Pathologist's Pocketbook (Waller et al. 2001). Methods for collecting and preserving different insect groups can be found in Bland and Jacques (1978), Borror et al. (1976) and British Museum (Natural History) (1974).

Back at base: treatment and dispatch of germplasm samples

This section gives a summary of the phytosanitary procedures involved in handling plant germplasm after it has been collected, along with brief notes on the dispatch of specimens for pest identification. For other aspects of the tasks that will need to be undertaken once back at base, see Chapter 28.

Inspection

Missions should carefully prepare germplasm samples before they are presented to quarantine authorities for inspection, treatment and certification.

-

Germplasm samples should be carefully inspected for pests, insects and mites as well as for lesions or colour patterns that might denote fungal, bacterial or viral pathogens. Where such pests, or symptoms of pests, are present, the pests and/or the symptom-bearing seeds should be removed.

-

Bare-rooted plants should be thoroughly washed to ensure they are free of soil, which might harbour nematodes and other soil-borne pathogens.

-

Seeds and pollen should be free of debris. If debris is present, it should be removed.

Phytosanitary treatments and certification

-

If mandatory treatments are prescribed on the import permit or endorsements are required, these should be given by the relevant government authority exactly as requested.

-

After treatments have been applied, they should be detailed on the phytosanitary certificate, together with any other endorsements requested by the importing country.

-

The phytosanitary certificate should bear the stamp of the organization issuing the certificate and should be signed by an authorized officer. Many countries are now issuing phytosanitary certificates electronically with stamps and signatures added in the computer (known as ePhytos). These are equally valid and may ease on-arrival arrangements because they are increasingly sent to the importing country digitally soon after they are issued.

-

Collectors should ensure that the phytosanitary certificate contains the following information:

-

name and address of the exporter

-

name and address of the consignee

-

number of samples of each species in the consignment

-

botanical name of each species

-

details of any phytosanitary treatments applied

-

additional endorsements required by the import permit

-

Documents accompanying germplasm consignments

-

The original phytosanitary certificate, plus a copy of the import permit, should accompany each consignment. Most importing countries will allow photocopies of import permits if there are multiple shipments, but it would be best to confirm this from the quarantine authorities of the importing country if there are any doubts. A copy of the import permit should be placed on the outside of the package so it can be forwarded to the plant quarantine authorities without the need to open it. A photocopy of the permit should be included inside the package in case of damage to the outside copy. However, this may vary from country to country. For example, regulations in the United States specify that all documents should be inside the package.

-

A copy of all documents sent with the consignments should be retained by the collector.

Preparation of samples for pest identification

Arrangements should be made in advance of the fieldwork with the institutes that are to receive samples for pest identification. Permits may have to be obtained to comply with the quarantine requirements of the country where samples are to be sent. Some additional points:

-

All material sent for identification purposes, whether preserved insects and mites, dried plant voucher specimens of diseased plants or living plant material for diagnosis of internal pathogens, should be labelled

-

with a reference number, as well as

-

the botanical name of the host plant

-

the locality where collected

-

the date of collecting

-

the name of the collector(s)

-

-

Collectors should keep a copy of the information accompanying each specimen.

-

Samples of seeds and pollen may have to be sent for viability testing, as well as for inspection for internally-borne pathogens, and weeds. Samples should be properly dried before dispatch.

-

Collectors should include the name of the person (and address) to whom the identification(s) should be sent.

Future challenges/needs/gaps

And what of the future? The challenge is for samples to move ever faster, and ever more safely, between countries, from places of collection to places of storage and other use. This requires collectors and quarantine officials to work together in more consistent and coherent ways – in itself a major challenge.

Collectors and the users of plant germplasm would like quarantine officials to act faster. Quarantine officials (ever mindful of their mandate to protect crops and indigenous flora from new pest incursions) need time if they are to do their job thoroughly. Tensions can arise from these, seemingly, different ways of viewing germplasm, but this is a false dichotomy. All sides have to work together if satisfactory outcomes are to be achieved: the rapid international movement of germplasm safe from risk.

If this is not achieved, there will be – or continue to be – adverse consequences. We know from anecdotal evidence that long delays in quarantine bring frustrations and, unfortunately, a temptation among some to short-circuit official systems, especially where these are not well developed. It is the responsibility of those sponsoring collecting missions to forbid such practices.

So are there ways to reduce the time it takes to process samples, check for associated pests? Some suggestions are obvious: crop-specific guidelines for testing germplasm for the pests of concern need to be produced, and they need to be updated constantly. Those produced by Bioversity International (also under its previous names as IBPGR and IPGRI) are expensive to produce and become outdated too soon. This needs to change. Documents need to be posted on the internet, and frequent revisions made as new data comes to hand. The linking of institutes – international and national – dealing with indexing technologies of specific crops needs to continue. And conformity of national quarantine regulations needs to be achieved. There are still countries that re-index samples, no matter that they have been indexed elsewhere, causing considerable frustration to would-be users.

Another question is whether molecular technologies can assist in speeding up the processing of germplasm samples. The most likely answer is both a “yes” and a “no”. Several current programmes that “fingerprint” and “bar-code” plants and animals will, undoubtedly, lead to speedy identifications of pests attached to germplasm being moved internationally. It may also speed up the process of determining whether pathogens are present within plant tissues.

The problem, however, is what to do about the detection of DNA within a plant that differs from that of the plant itself, particularly if there are no symptoms of any kind. Currently, plants that are symptomless after months or years (most often a crop cycle) in quarantine are released to the importer. In future, national phytosanitary officials may have to deal with the quandary of what to do about symptomless plants containing apparently alien DNA. There is no guarantee that once released into a new environment the endophytic organism will not be transferred to another plant (perhaps by an insect vector) and become a pest. Decision making in this area is set to become extremely difficult.

As mentioned already in this chapter, the internet has grown greatly over the years since this book was first published, and is now of immense value to researchers and national phytosanitary officials alike. They now have almost instant access to all the knowledge available on a particular organism, much of it being kept up to date. Perhaps the next phase, already beginning in some countries, will be to enable researchers, industry and governments to collaborate, use expertise, share data and information, and generate intelligence through the development of information technologies akin to the popular social networks. An example of this is the web portal of the Australian Biosecurity Intelligence Network (ABIN): www.abin.org.au/web/index.html.

Development of biosecurity networks will be a challenge within countries where researchers may guard certain information prior to publication, but it will be even more challenging between countries where the trade implications of the presence or absence of a pest can have huge economic consequences. Nevertheless, the benefits of information sharing are already self-evident following the growth of the internet, and it is to be hoped that attempts at greater information sharing through networking will be equally positive.

Conclusions

Countries throughout the world are keen to safeguard agriculture, forestry and the environment from potentially threatening invasive pest species. This commitment is regulated under the International Plant Protection Convention with support, in recent years, from the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (the SPS Agreement). Governments apply measures for food safety and animal and plant health – sanitary and phytosanitary measures – to impede the spread of pests. Collectors of germplasm must be aware of these developments, and the potential harm that the unrestricted movement of germplasm could cause. They must ensure that samples conform to standards set under both national legislation and international regulations. Failure to do this could jeopardize collecting missions.

Back to list of chapters on collecting

References and further reading

General

AAB. 1985 et seq. Descriptions of Plant Viruses. Association of Applied Biologists, Wellesbourne, UK.

Altieri MA. 1993. Ethnoscience and biodiversity: key elements in the design of sustainable pest management systems for small farmers in developing countries. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 46:257–272.

Bland RG, Jacques HE. 1978. How To Know Insects. WC Brown Company Publishers, Dubuque, Iowa.

Borror DJ, Delong DM, Triplehorn CA. 1976. An Introduction to the Study of Insects. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York.

British Museum (Natural History). 1974. Insects. Instructions for collectors No.4a. British Museum (Natural History), London.

Brunt AA, Crabtree K, Gibbs A. 1990. Viruses of Tropical Plants. CAB International, Slough, UK.

Brunt AA, Crabtree K, Dallwitz M, Gibbs A, Watson L, Zurcher E, editors. 1996. Plant Viruses Online: Descriptions and Lists from the VIDE Database. CAB International, Wallingford, UK. Available online (accessed 15 August 2011): www.agls.uidaho.edu/ebi/vdie/refs.htm.

CMI/AAB. 1970-1984. Descriptions of Plant Viruses. Sets 1–18. CAB International and Association of Applied Biologists, Slough and Wellesbourne, UK.

FAO. 1993. Directory of Regional Plant Protection Organizations and National Plant Quarantine Services. AGPP/Misc /93/1. FAO, Rome.

FAO. 2011. International Standards for Phytosanitary Certificates. ISPM 12. FAO, Rome. Available online (accessed 15 August 2011): https://www.ippc.int/file_uploaded/1307528241_ISPM_12_2011_En_2011-05-03(Corre.pdf.

Hall GS, Hawksworth DL. 1990. International Mycological Directory. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Hewitt WB, Chiarappa L. 1977. Plant Health and Quarantine in International Transfer of Genetic Resources. CRC, Cleveland, Ohio.

IIE. 1968 et seq. Distribution Maps of Pests. Series A (Agriculture). International Institute of Entomology (formerly Commonwealth Institute of Entomology) and CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

IIP. 1972 et seq. IIP Descriptions of Plant-Parasitic Nematodes. International Institute of Parasitology (formerly Commonwealth Institute of Helminthology) and CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

IMI. 1942 et seq. IMI Distribution Maps of Plant Diseases. International Mycological Institute (formerly Commonwealth Mycological Institute) and CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

IMI. 1964 et seq. IMl Descriptions of Fungi and Bacteria. International Mycological Institute (formerly Commonwealth Mycological Institute) and CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

IPPC. 2010. Glossary of Phytosanitary Terms. ISPM No. 5. International Plant Protection Convention, Rome. Available online (accessed 15 August 2011): https://www.ippc.int/file_uploaded/1273490046_ISPM_05_2010_E.pdf.

Johnston A, Booth C. 1983. Plant Pathologist's Pocketbook. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Nelson SC, Bushe BC. 2006. Collecting Plant Disease and Insect Pest Samples for Problem Diagnosis. SCM-14. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii. Available online (accessed 29 August 2011): www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/SCM-14.pdf.

Sonoda RM. 1979. Collection and preservation of insects and pathogenic organisms. In: Mott GO, Jimenez A, editors. Handbook for the Collection, Preservation and Characterization of Tropical Forage Germplasm Resources. CIAT, Cali, Colombia.

Waller JM, Lenné JM, Waller S. 2001. Plant Pathologists’ Pocketbook. 3rd Edition. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

American Phytopathological Society online bookshop: www.cplbookshop.com/glossary/G583.htm

Australian Biosecurity Intelligence Network (ABIN): www.abin.org.au/web/index.html

Bioversity International descriptor lists: www.bioversityinternational.org/research/conservation/sharing_information/descriptor_lists.html

CABI Crop Protection Compendium (CPC): www.cabi.org/cpc

Crop Genebank Knowledge Base: http://cropgenebank.sgrp.cgiar.orgindex.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=137&Itemid=238&lang=english

Descriptions of fungi and bacteria (IMI): www.cabi.org/default.aspx?site=170&page=1016&pid=2214

Descriptions of plant viruses (CMIIAAB): www.dpvweb.net

Distribution maps of pests (lIE): www.cabi.org/default.aspx?site=170&page=1016&pid=2212

Distribution maps of plant diseases (IMI): www.cabi.org/default.aspx?site=170&page=1016&pid=2210

FAO/IPPC list of plant-protection services worldwide: https://www.ippc.int/index.php?id=1110520&no_cache=1&type=contactpoints&L=0

Global Plant Clinic: www.cabi.org/default.aspx?site=170&page=1017&pid=2301

International Plant Protection Convention (lPPC): https://www.ippc.int/index.php?id=1110589&L=0

Natural History Museum, South Kensington, UK: www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/contact-enquiries/identification-and-general-science-enquiries/index.html

Examples of useful databases on plants and pests

|

Arthropods of Economic Importance: Agromyzidae |

|

|

Arthropods of Economic Importance: Diaspididae |

http://nlbif.eti.uva.nl/bis/diaspididae.php?menuentry=inleiding |

|

Australian Faunal Director |

www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/abrs/online-resources/fauna/afd/home |

|

Databases and Publications from Kew |

www.kew.org/science-research-data/databases-publications/index.htm |

|

Descriptions of Plant Viruses |

|

|

Diseases and disorders of cultivated palms |

|

|

EcoPort |

|

|

EPPO Database on Diagnostic Expertise |

|

|

Fauna Europea |

|

|

Flora of New Zealand |

|

|

ICTVdB Index of Viruses |

|

|

Lucidcentral Key Search |

www.lucidcentral.com/Keys173/SearchforaKey/tabid/217/language/en-US/Default.aspx |

|

Index Fungorum |

|

|

Mansfeld's World Database of Agricultural and Horticultural Crops |

http://mansfeld.ipk-gatersleben.de/pls/htmldb_pgrc/f?p=185:3:4166990628405234 |

|

NLBIF Biodiversity Data Portal |

|

|

Landcare Research (New Zealand) |

|

|

Pacific Islands Pest List Database |

|

|

Plant Viruses Online |

|

|

The Global Lepidoptera Names Index |

www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/lepindex/index.html |

|

USDA ARS Fungal Databases |

|

|

USDA ARS Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN) Taxonomy for Plants |

|

|

USDA ARS Systematic Entomology Laboratory |

|

|

Wikispecies |

FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm Series

Acacia spp.

Old KM, Vercoe TK, Floyd RB, Wingfield MJ, Roux J, Neser S, editors. 2002. Acacia spp. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 20. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Allium spp.

Diekmann M. 1997. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Allium spp. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 18. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Cacao

Frison EA, Diekmann M, Nowell D, editors. 2000. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Cocoa Germplasm. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 20. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Cassava

Frison EA, Feliu E, editors. 1991. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Cassava Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Citrus

Frison EA, Taber M, editors. 1991. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Citrus Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Coconut

Frison EA, Putter CAJ, Diekmann M, editors. 1993. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Coconut Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Edible aroid

Zettler FW, Jackson GVH, Frison EA. 1989 FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Edible Aroid Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Eucalyptus spp

Ciesla WM, Diekmann M, Putter CAJ, editors. 1996. Eucalyptus spp. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 17. FAO/IPGRI, ACIAR & ASEAN, Rome.

Grapevine

Frison EA, lkin R, editors. 1991. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Grapevine Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Legumes

Frison EA, Bos L, Hamilton RI, Mathur SB, Taylor JD, editors. 1990. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Legume Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Musa spp.

Diekmann M, Putter CAJ. 1996. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Musa Germplasm. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 15. 2nd Edition. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Pinus spp.

Diekmann M, Sutherland JR, Nowell DC, Morales FJ, Allard G, editors. 2002. Pinus spp. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 21. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Potato (Solanum tuberosum)

Jeffries C J. 1998. Potato. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 19. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Small fruits

Diekmann M, Frison EA, Putter CAJ, editors. 1994. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Small Fruit Germplasm. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Small grain temperate cereals

Diekmann M, Putter CAJ, editors. 1995. Small Grain Temperate Cereals. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 14. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Stone fruits

Diekmann M, Putter CAJ, editors. 1994. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Stone Fruit Germplasm. FAO / IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm No. 16. FAO/IPGRI, Rome.

Sugarcane

Frison EA, Putter CAJ, editors. 1993. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Sugarcane Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas)

Moyer JW, Jackson GVH, Frison EA. 1989. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Sweet Potato Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Vanilla

Pearson MN, Jackson GVH, Zettler FW, Frison EA. 1991. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Vanilla Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

Yam (Dioscorea spp.)

Brunt AA, Jackson GVH, Frison EA. 1989. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Yam Germplasm. FAO/IBPGR, Rome.

The American Phytopathological Society (APS) publications on the identification of plant diseases (www.apsnet.org/publications/Pages/default.aspx)

|

Compendium of Corn Diseases (Third Edition) |

Shade Tree Wilt Diseases |

Appendix 17.1: IPPC Model Phytosanitary Certificate

(Download IPPC Model Phytosanitary Certificate (0.9 MB) for printing purposes)

|

|

Source: FAO (2011) |

Chapter 25: Collecting pollen for genetic resources conservation

Gayle M. Volk

National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation USDA-ARS, Fort Collins, USA

E-mail: Gayle.Volk(at)ars.usda.gov

|

2011 version |

1995 version |

||

|

Open the full chapter in PDF format by clicking on the icon above. |

|||

This chapter is a synthesis of new knowledge, procedures, best practices and references for collecting plant diversity since the publication of the 1995 volume Collecting Plant Genetic Diversity: Technical Guidelines, edited by Luigi Guarino, V. Ramanatha Rao and Robert Reid, and published by CAB International on behalf of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) (now Bioversity International), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The original text for Chapter 25: Collecting Pollen for Genetic Resources Conservation, authored by F. A. Hoekstra, has been made available online courtesy of CABI. The 2011 update of the Technical Guidelines, edited by L. Guarino, V. Ramanatha Rao and E. Goldberg, has been made available courtesy of Bioversity International.

Please send any comments on this chapter using the Comments feature at the bottom of this page. If you wish to contribute new content or references on the subject please do so here.

Back to list of chapters on collecting

|

|

|

Germinating pecan pollen. (Photo: J. Waddell/USDA-ARS - National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation). |

Abstract

Pollen is a useful source of diverse alleles within a genepool and so may be an effective propagule for genebanks. The ease of pollen storage and shipment and the potential for its immediate use provide researchers with increased options when designing their breeding programs. Methods for pollen collection, desiccation, viability testing and longevity assessment have been developed for many species of interest, and have revealed the critical importance for increased longevity by using high quality pollen desiccating it sufficiently in a rapid manner and subsequently storing it at very low temperatures. Reliable viability assessments are dependent upon adequate rehydration and the use of reliable stains, in vitro germination assays or in vivo pollination experiments. Pollen preservation in genebanks will likely be implemented as standard procedures for handling and assessing it are developed.

Current Status

Advantages to the use of pollen

-

Genebanked pollen can be made available to breeders upon request. For tree species, this obviates the need for growing the male parents in the breeding orchards. It allows for wide hybridization across seasonal and geographical limitations, and reduces the coordination required to synchronize flowering and pollen availability for use in crosses (Bajaj 1987). With adequate pollen available, one can also load additional pollen onto stigmas to increase pollination and yield.

-

Pollen is available for research programs. As single cells, pollen provides a simple model system for research on conservation. Storage of pollen within genebanks also ensures its availability year-round for basic biology and allergy research programs (Shivanna 2003).

-

Pollen captures diversity within small sample sizes, and documentation is available for long-term survival of pollen from many diverse species (table 25.1). Pollen also serves as a source of genetic diversity in collections where it is hard to maintain diversity with seeds (species of low fecundity, large seeds, or seeds that require an investment of labour to store).

-

Pollen can also be shipped internationally, often without threat of disease transfer (Hoekstra 1995).

Table 25.1. A Selection of Species for Which Pollen Can Be Successfully Stored at –80°C or Liquid Nitrogen (LN) Temperatures

|

Species |

Storage duration |

Temperature |

Viability test |

Reference |

|

Actinidia |

1 y |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Abreu and Oliveira 2004 |

|

Aechmea |

15 min |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Parton et al. 2002; Parton et al. 1998 |

|

Allium |

1 y |

LN |

pollination |

Ganeshan 1986b |

|

Beta |

17 y |

LN |

FDA, MTT, pollination |

Panella et al. 2009 |

|

Beta |

1 y |

LN |

pollination |

Hecker et al. 1986 |

|

Carica |

485 d |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Ganeshan 1986a |

|

Carya |

13 y |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Sparks and Yates 2002 |

|

Carya |

1 y |

LN |

pollination |

Yates and Sparks 1990 |

|

Carya |

3 y |

-80 |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Yates and Sparks 1990 |

|

Citrus |

3.5 y |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Ganeshan and Alexander 1991 |

|

Clianthus |

3 h |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Hughes et al. 1991. |

|

Dioscorea |

2 y |

-80 |

acetocarmine |

Ng and Daniel 2000 |

|

Elaeis |

8 y |

LN |

FDA, in vitro germ |

Tandon et al. 2007 |

|

Gladiolus |

10 y |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Rajasekharan et al. 1994 |

|

Glycine |

7 d |

LN |

pollination |

Tyagi and Hymowitz 2003 |

|

Guzmania |

15 min |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Parton et al. 2002 |

|

Humulus |

2 y |

LN |

pollination |

Haunold and Stanwood 1985 |

|

Juglans |

2 y |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Farmer and Barnett 1974 |

|

Juglans |

1 y |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Luza and Polito 1987 |

|

Lycopersicon |

5 wk |

-80 |

pollination |

Sacks and St. Clair 1996 |

|

Lycopersicon |

22 mo |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Karipidis et al. 2007 |

|

Olea |

1 h |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Parfitt and Almehdi 1984a |

|

Panax |

11 mo |

LN |

stain, in vitro germ, pollination |

Zhang et al. 1993 |

|

Persea |

1 y |

LN |

pollination |

Sedgley 1981 |

|

Phoenix |

435 d |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Tisserat et al 1983 |

|

Protea |

1 y |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Van der Walt and Littlejohn 1996 |

|

Prunus |

12 mo |

-80 |

in vitro germ |

Martinez-Gómez et al. 2002 |

|

Prunus |

1 h |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Parfitt and Almehdi 1984b |

|

Pyrus |

3 y |

LN |

pollination |

Akihama and Omura 1986 |

|

Rosa |

8 wk |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Marchant et al. 1993 |

|

Rosa |

1 y |

LN |

hanging drop, fertilization |

Rajasekharan and Ganeshan 1994 |

|

Solanum |

10 min |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Towill 1981 |

|

Tillandsia |

15 min |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Parton et al. 2002 |

|

Vitis |

64 wk |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Ganeshan 1985a |

|

Vitis |

5 y |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Ganeshan and Alexander 1990 |

|

Vitis |

1 h |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Parfitt and Almehdi 1983 |

|

Vriesea |

15 min |

LN |

in vitro germ |

Parton et al. 2002 |

|

Zea |

120 d |

LN |

in vitro germ, pollination |

Barnabás and Rajki 1976 |

Disadvantages to the use of pollen

-

Limited pollen production in some species. The primary limitation in the routine implementation of pollen storage within genebanks is the difficulty in obtaining adequate quantities of pollen for many species.

-

Labour-intensive collection or processing. For some species, pollen is readily available, but resources to accumulate and process enough pollen for routine storage and distribution are inadequate.

-

No standardized processing or viability-testing protocols. Processing and viability-testing methods have not been documented and standardized in a manner similar to that of seed testing.

-

Regeneration of aged pollen. Seed regeneration can often be performed directly using the seed samples in storage. For pollen, associated mother plants are necessary to replenish pollen supplies when quantities are depleted or have deteriorated (Schoenike and Bey 1981).

Pollen collection

Collected pollen serves to maintain and preserve the alleles of an individual or population. Sampling strategies have often recommended collecting a set number of individuals per population to ensure that the common alleles are captured. The exact number of individuals that most effectively captures the genetic variation is dependent upon the genetic diversity and life-history traits of the species (Lockwood et al. 2006). Namkoong (1981) suggests that collecting pollen from a single tree easily captures the alleles for that genotype; however, it is recommended that a minimum of 68 trees be sampled to represent a wild population. Pollen can also be collected from individual trees within a genebank both to conserve alleles specific to each individual and to provide male gametes for breeding purposes. Although only small quantities of pollen are required to capture the genes of an individual, because of the challenges of pollen collection and processing, it might be more efficient to collect larger quantities to ensure its long-term availability to the user community.

Pollen should be harvested soon after anthesis, usually in the morning hours (Ganeshan et al. 2008; Towill 2004). Shelf life is short for pollen collected from immature, aged, or weather-damaged anthers (Towill 1985). It is usually more practical to collect anthers in the field and then separate the pollen grains from the anthers in a laboratory environment soon after collection. All pollen must be processed immediately (within hours) to ensure maximum potential longevity.

|

|

|

Storage of pollen for long-term preservation |

Pollen desiccation

Successful pollen genebanking is dependent upon achieving long-term survival of stored pollen. Water content, cooling rate and storage temperature all affect the longevity of stored pollen (Buitink et al. 1996, 2000). Field conditions and relative humidity at the time of harvest affect the pollen moisture content, and germinability is impaired when pollen is kept for any length of time in wet or high-humidity conditions (Hoekstra 1986). Pollen ages quickly when held at 24°C and 75% relative humidity (RH) (Van Bilsen et al. 1994).

For desiccation-tolerant pollen, it is critical that the pollen be dried to a target moisture content soon after harvest. Depending on species, successful long-term storage requires that the moisture content be reduced to or below levels at which there is no free water (Priestley 1986). For many species, pollen can be dried to water contents of 0.05 g H2O g-1 dry weight (DW) without a loss in viability (Hoekstra 1986). This can be achieved by drying overnight in a low-humidity room environment or over salt chambers that are maintained at RH of about 30%. Equilibration over salt slurries, such as magnesium chloride or calcium nitrate, prevents damage that could result from over drying within ovens. It is a straightforward method to control moisture content in diverse laboratory environments (Connor and Towill 1993; Towill 1985).

Anthers or pollen grains can also be dried over silica gel at room temperature (Ganeshan 1985; Parfitt and Ganeshan 1989; Parton et al. 1998; Sacks and St. Clair 1996; Van der Walt and Littlejohn 1996). Martinez-Gómez et al. (2002) successfully desiccated almond pollen with silica gel for 48 hours at 22°C for long-term storage. Sato et al. (1998) dehydrated anthers at 20°C for 16–24 hours at RH of 15% or 32% prior to storage. Although some researchers have demonstrated successful desiccation through the use of freeze-driers for pollen desiccation, concerns have arisen with regard to maintaining viability in pollen that has been frozen prior to dehydration (Ganeshan and Alexander 1986, 1987; Perveen and Khan 2008). Towill (1985) argued that vacuum drying was as effective as freeze-drying for maintaining pollen viability. Although air at low RH will increase the drying rate, pollen must be removed before it dries to a lethal moisture level (1% to 2 % for peach and pine, 3.5% for coconut pollen) (Towill 1985). Pollen can be successfully dried in 35°C ovens, but care must be taken not to over dry under these conditions (Yates et al. 1991).

Rapid air-drying can also be achieved by using specialized pollen-dryers that blow air at 20% to 40% RH and 20°C, to quickly reduce moisture content in the pollen of Poaceae species, including Avena, Pennisetum, Saccharum, Secale, Triticum, Tricosecale and Zea (Barnabás and Kovacs 1996). Maize pollen is easily stored when quickly dried to 0.19 g H2O g-1 DW (Buitink et al. 1996).The longevity of the pollen from these desiccation-sensitive species, and its tolerance to freezing temperatures, has been extended as a result of using rapid dehydration methods. The principle of rapid drying (flash drying) has successfully been documented in recalcitrant seeds, where it was shown that one could dry to a much lower water content if one did it rapidly (Pammenter et al. 1991).

Storage temperature

It is possible to store pollen of many species at temperatures between 4°C and –20°C for the short-term. Dry pollen that is kept at between 4°C and –20°C remains viable for a few days to a year, which may be adequate for use in breeding programs (Hanna and Towill 1995).

Long-term viability can be maintained by storing pollen at –80°C or LN temperatures (–196°C) (Hanna and Towill 1995). Once desiccated, pollen can be dispensed into cryovials for long-term storage in LN or LN vapour. Precise labelling of vials and storage locations is recommended to aid in future retrieval of samples. Vials can then be placed in boxes or cryocanes and directly immersed in the liquid or vapour phase of liquid nitrogen (Barnabás and Kovács 1996; Ganeshan et al. 2008; Hanna and Towill 1995; Connor and Towill 1993).

Pollen rehydration

Dried pollen is susceptible to injury from rapid water update during rehydration (also known as imbibitional injury) (Hoekstra and Van der Wal 1988), which can severely reduce germination and lead to low viability counts if vital staining (stains to identify living cells) is used to assess it. Low temperatures can exacerbate imbibitional damage, which is believed to arise from mechanical damage to the plasma lemma as polar lipids undergo phase changes as a result of fluctuations in temperature, water content and sugars (Hoekstra et al. 1992; Hoekstra and Van der Wal 1988; Crowe et al. 1989). Slow rehydration ameliorates imbibitional damage to pollen grains and this is usually accomplished by placing the pollen in a humid environment prior to direct liquid exposure (Hoekstra and Van der Wal 1988; Luza and Polito 1987; Parton et al. 2002). Pollen rehydration can be as straightforward as placing open vials of pollen in 100% humidity environments for 1 to 4 hours at room temperature (Connor and Towill 1993; Hanna and Towill 1995).

Although suboptimal storage conditions may affect pollen vigour before a measurable change in pollen viability is observed, most studies make use of viability assessments (Shivanna et al. 1991). Pollen viability can be measured by vital staining pollen grains, by germinating pollen grains in vitro, or by demonstrating successful fertilization and seed development in plants.

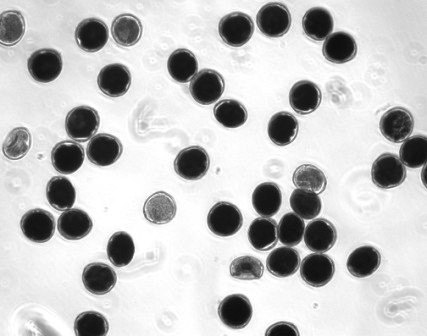

Pollen viability

|

|

|

Viability staining (thiazolyl blue tetrazolium) for pecan pollen grains (photo: John Waddell, USDA-ARS-National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation). |

Staining

One commonly used vital stain is the fluoregenic ester, fluorescein diacetate (FDA). This test measures membrane integrity. Pollen grains fluoresce green when a cellular esterase cleaves the FDA (Heslop-Harrison and Heslop-Harrison 1970). Since this assay is dependent upon functional membranes, the osmoticum of the FDA staining solution is critical; stain is often dissolved in a 10% to 20% sucrose solution containing boric acid and calcium nitrate to minimize plasmolysis and membrane leakage.

Comparisons of viability determined through the use of FDA or tetrazolium and those obtained using in vitro germination or in vivo fertilization tests reveal consistently high correlations, provided pollen is adequately rehydrated prior to testing (Firmage and Dafni 2001; Khatun and Flowers 1995; Rodriguez-Riano and Dafni 2000; Shivanna and Heslop-Harrison 1981). FDA has occasionally been shown to give false negative results, where viable pollen appears dead (Heslop-Harrison et al. 1984).

Several tetrazolium-based stains are available for testing pollen viability (Norton 1966). The 3 (4,5-dimethyl thiazolyl 1-2) 2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) test was shown to give the most dependable results in a comparison trial using plum pollen (Norton 1966). In general, tetrazolium tests measure the ability to reduce colourless tetrazolium to coloured formazan, thus identifying pollen that has a capacity for oxidative metabolism (Hauser and Morrison 1964).

Many other vital stains have been developed and proposed over the past 50 years. Stains such as Alexander‟s, acetocarmine, aniline blue and X-gal have been shown to be successful identifiers of viability for relatively few species or under specialized conditions (Rodriguez-Riano and Dafni 2000). Viability results obtained with these stains may not correlate well with in vitro germination assays (Towill 1985).

In vitro germination

Pollen can be germinated in vitro by placing pollen grains onto a medium and measuring the elongation of the pollen tube after a few hours of imbibition. Pollen tubes that elongate to a length that is at least the diameter of the pollen grain are considered viable (Dafni and Firmage 2000). Automated counting procedures using morphometry software result in pollen counts that are within 5% of visual observations and allow the determination of pollen tube length in addition to the data obtained by eye on tube presence or absence (Pline et al. 2002). These automated systems may expedite time-consuming assays of in vitro pollen germination. As for viability testing, it is important to implement repeatable and standardized methods and to use dead pollen samples as controls.

The optimal temperature for in vitro germination assays can be species dependent. The pollen from many species germinates well at 25°C; however, differences exist. For example, cotton pollen has an optimum germination temperature of 28°C to 31°C (Burke et al. 2004). Hence, for the purpose of pollen conservation, such information should be known for the target species.

In vitro germination methods utilize pollen immersed in aerated solutions, “hanging” drops, or dispersed on solidified medium. The medium is often that described by Brewbacker and Kwack (1963) or a slight modification thereof. Boric acid, calcium nitrate and sucrose concentrations in the medium might have to be optimized according to species (Bolat and Pirlak 1999; Heslop-Harrison 1992). The hanging-drop method involves the placement of a slide or coverslip with liquid medium and pollen inverted over a 100% humidity chamber (Rajasekharan and Ganeshan 1994). For observation, the slide is returned to an upright position and observed under a microscope.

Pollination

Testing viability by observing pollen tube elongation within the stigma or fertilization and subsequent seed production is the most time-intensive way to determine pollen viability; however, these kinds of tests are also the most relevant to demonstrate the adequacy of the pollen for use. Rehydrated pollen can be placed on the stigmas of live plants, and tube length is measured after a pre-determined time interval (Dafni and Firmage 2000). Ideally, successful fruit set and seed production occurs after pollination with conserved pollen. Marquard (1992) demonstrated that high levels of viability are not required. Fruit set occurred when stigmas were treated with only 5% viable pollen. When pollen appears viable based on germination tests, it is often also viable in fertilization assays.

Pollen longevity

The longevity of pollen is dependent upon many factors specific to cultivars or species as well as handling procedures, as discussed here (Ganeshan and Alexander 1991; Hanna and Towill 1995). The presence of sucrose and polysaccharides in the pollen has been correlated with protection of membranes from desiccation or temperature stress and may confer greater longevity (Dafni and Firmage 2000; Hoekstra et al. 1989). High-quality pollen dehydrated to an optimal moisture content and stored at LN temperatures has been documented to store for well over 10 years (Panella et al. 2009; Sparks and Yates 2002). The low temperature reduces the molecular mobility in the cytoplasm, which may be a controlling factor in pollen longevity (Buitink et al. 2000). The aging of dried pollen is likely caused by oxidative reactions, and pollens with higher levels of unsaturated fatty acids usually have a shorter shelf life (Hoekstra 2005). Correspondingly, pollen longevity may be further improved by storing desiccated pollen in an oxygen-free atmosphere (Hoekstra 1992).

Most reports describing pollen survival after LN exposure state viability levels after determined lengths of time, often without initial germination data. These end-point levels serve to demonstrate that the tested length of storage is possible, but they do not describe the longevity of the pollen per se. Table 25.1 demonstrates the diverse range of species for which pollen can be placed at LN temperatures. According to current information, it is clear that both desiccation-tolerant and non-desiccation-tolerant pollen types can be stored for over 10 years under controlled conditions (Barnabás1994; Barnabás and Kovács 1996; Shivanna 2003). Thus, despite additional challenges that may be present in storing desiccation-sensitive pollen, it is possible. Additional research is needed to determine how long both types of pollen will remain viable under these conditions.

Future challenges/needs/gaps

Technologies for successful pollen conservation have been developed and are available. A set of standardized methods to process pollen types with different physiologies is needed to make pollen storage a routine effort in genebanks. For many species in need of pollen conservation, we need to know more about the phenology of pollen production so that we can properly time pollen harvests. Standards should be developed for pollen collection, processing and storage of desiccation-tolerant and non-desiccation-tolerant pollen types. Determination of pollen genebanking standards is an initial step towards implementing pollen genebanking methods.

The literature currently lists the age and viability of pollen from many species stored at LN temperatures (table 25.1) (Barnabás and Kovács 1996; Ganeshan and Rajashekaran 2000; Hanna and Towill 1995; Towill 1985). However, the viability over time, or longevity, of pollen stored under LN genebanking conditions has not been thoroughly evaluated. In addition, detailed biophysical studies should be pursued to determine the optimal water content, desiccation rates and longevity relationships for various pollen types. Longevity must be known in order to ascertain the cost and benefits of genebanking pollen.

Conclusions

There are abundant reports in the literature of many successes for testing pollen viability and temperature exposure. Many of the reported data and methods are difficult to replicate when basic parameters such as initial water content, equilibrated (desiccated) water content and rehydration methods are not described (Dafni and Firmage 2000). It is clear that the physiological state of the pollen at the time of collection and the handling of that pollen within the first few days after collection will determine its potential for long-term survival under optimum conditions. Detailed reporting of handling upon harvest is essential if standardized methods are to be developed. Confirmation that reported staining, in vitro germination and in vivo germination results are correlated increases confidence in and the repeatability of the reported data.

Despite the challenges, pollen is a valuable genetic resource for conservation. It provides breeders and researchers with an additional, complementary, propagule that may be immediately useful in their programs, although the feasibility of pollen collection and preservation varies among plant species.

Back to list of chapters on collecting

References and further reading

Abreu I, Oliveira M. 2004. Fruit production in kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) using preserved pollen. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 55:565–569.

Akihama T, Omura M. 1986. Preservation of fruit tree pollen. In: Bajaj YPS, editor. Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry. Vol. 1: Trees. Springer Verlag, Berlin. pp.101–112.

Bajaj YPS. 1987. Cryopreservation of pollen and pollen embryos, and the establishment of pollen banks. International Review of Cytology 107:397–420.

Barnabás B. 1994. Preservation of maize pollen. In: Bajaj YPS, editor. Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry. Vol. 25. Springer Verlag, Berlin. pp. 608–618.

Barnabás B, Kovács G. 1996. Storage of pollen. In: Shivanna KR, Sawhney VK, editors. Pollen Biotechnology for Crop Production and Improvement. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. pp. 293–314.

Barnabás B, Rajki E. 1976. Storage of maize (Zea mays L.) pollen at -196oC in liquid nitrogen. Euphytica 25:747–752.

Bolat I, Pirlak L. 1999. An investigation on pollen viability, germination and tube growth in some stone fruits. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 23:383–388.

Brewbacker JL, Kwack BH. 1963. The essential role of calcium ion in pollen germination and pollen tube growth. American Journal of Botany 50:859.

Buitink J, Leprince O, Hemminga MA, Hoekstra FA. 2000. The effects of moisture and temperature on the ageing kinetics of pollen: interpretation based on cytoplasmic mobility. Plant, Cell and Environment 23:967–974.

Buitink J, Walters-Vertucci C, Hoekstra FA, Leprince O. 1996. Calorimetric properties of dehydrating pollen. Plant Physiology 111:235–242.

Burke JJ, Velten J, Oliver MJ. 2004. In vitro analysis of cotton pollen germination. Agronomy Journal 96:359–368.