CGKB News and events

Chapter 13: Published information resources for plant germplasm collectors

M. Garruccio

Bioversity International, Rome, Italy

E-mail: m.garruccio(at)cgiar.org

|

2011 version |

1995 version |

||

|

Open the full chapter in PDF format by clicking on the icon above. |

|||

This chapter is a synthesis of new knowledge, procedures, best practices and references for collecting plant diversity since the publication of the 1995 volume Collecting Plant Genetic Diversity: Technical Guidelines, edited by Luigi Guarino, V. Ramanatha Rao and Robert Reid, and published by CAB International on behalf of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) (now Bioversity International), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The original text for Chapter 13: Bibliographic Databases for Plant Germplasm Collectors, authored by J .A. Dearing and L. Guarino, has been made available online courtesy of CABI. The 2011 update of the Technical Guidelines, edited by L. Guarino, V. Ramanatha Rao and E. Goldberg, has been made available courtesy of Bioversity International.

Please send any comments on this chapter using the Comments feature at the bottom of this page. If you wish to contribute new content or references on the subject please do so here.

Back to list of chapters on collecting

Abstract

Widespread access to the internet and the technological changes we have seen over the last 16 years, since the first edition of this collecting manual, have dramatically altered the way people access and use information. They have also changed the paradigm of scientific publishing and research. Tools and resources for accessing information on plant genetic resources have grown and evolved from being mainly traditional and paper-based to sophisticated web-based platforms that provide the researcher with many features. Other tools, such as the social media platforms that have recently emerged, allow researchers to connect and collaborate with their peers regardless where they are located in the world. This paper looks at selective trends and movements that have had an impact on the paradigm of scientific publishing and research in the last 16 years, and, within this context, highlight authoritative web-based information resources for those working in the area of plant genetic resources.

|

Most websites nowadays offer direct access to the latest web tools and social media. |

Introduction

Sixteen years has passed since the publication of the first edition of Collecting Plant Genetic Diversity : Technical Guidelines. In that time, widespread access to the internet, along with other technological changes, have dramatically altered the way people access and use information. They have also changed the paradigm of scientific publishing and research. Sixteen years ago, a researcher would have primarily consulted hardcopies of abstract journals or standalone databases that were available at a library for his/her research purposes. The completed research would then be disseminated mainly via the medium of publishing in a scientific journal (available only in hardcopy). The same researcher would then meet and collaborate with peers, face to face, at conferences.

This scenario of only 16 years ago is difficult to grasp, when today, searching for information on search engines such as Google has become second nature, as has our ability to access, disseminate and generate information. The internet, today, can allow that same researcher to make his/her work available to the world, anywhere, at any time, in many different formats. It can also allow the researcher the possibility of collaborating with peers on different electronic platforms without leaving his/her desk.

While accessing the internet has now become part of our daily lives, the unprecedented amounts of information a researcher is faced with can be daunting. Together, published and professional web content is estimated to generate about 5 gigabytes/day, whereas user-generated content is created at the rate of about 10 gigabytes/day and growing. (Agichtein et al. 2009). These figures make it eminently clear that filters are required in order to access high-quality, authoritative scientific information. There is also a need to explore the concept that scientific research is now being carried out, communicated and disseminated by social media tools that previously did not exist. The researcher today has the opportunity to access information from many different formats, not just the traditional bibliographic databases that were discussed in the 1995 edition of these technical guidelines.

The two main objectives of this chapter are (1) to look at selective trends and movements that have had an impact on the paradigm of scientific publishing and research in the last 16 years and (2) within this context, to highlight authoritative web-based information resources for those working in the area of plant genetic resources.

Current status

The focus of this chapter is on the main trends and phenomena that have emerged over the last 16 years: (1) using search engines more effectively, (2) open-access resources, (3) social-media tools, (4) bibliographic databases and (5) reference-management systems.

Web searching: how to improve search results

Nowadays most people use the internet for their research purposes, but how effectively? If we are to examine the daunting statistics given to us by Agichtein et al. (2009), we realise that learning how search engines respond to queries can make a significant difference in the results we encounter when searching the web. Learning a few quick shortcuts and tricks can assist the researcher in finding more relevant and targeted information. Most of the major search engines have tutorials and guides on how to improve search results and retrieve relevant information. Table 13.1 provides a good overview of the search engines that are most used and where to locate their on-line tutorials and cheat sheets.

Table 13.1: Web Searching: Improving Your Search Results

This table provides information on where to locate search tips, shortcuts and cheat sheets for the three major search engines currently in use. Learning to use these tips will improve the relevance of research results.

|

Search engine |

Search tips, shortcuts and cheat sheets |

|

|

Using Yahoo! Search (covers simple, advanced searching, plus tips and preferences) |

||

|

Search tips and techniques |

||

Note: Access date for this information was 30 June 2011.

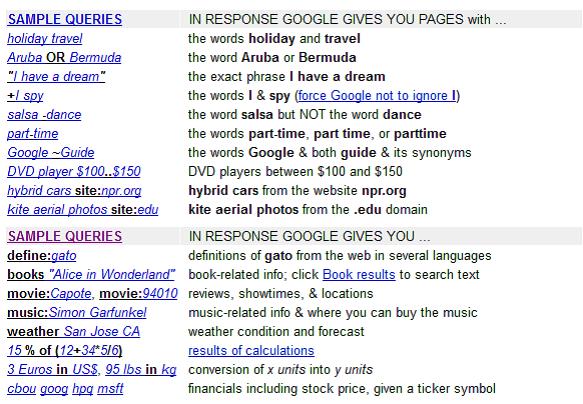

Google is the most used search engine. As of December 2010, its market share was 90.57% (StatCounter 2011). Nancy Blachmann from GoogleGuide.com has developed a simple and clear overview of the responses Google will provide depending on how one formulates the query (figure 13.1).

These searching tips can also be used when searching across portals such as Google Scholar, which is one of the major free web search engines that indexes the full text of mainly scholarly literature across an array of disciplines. It allows the researcher to search across many sources (e.g., professional societies, universities, academic publishers) from just one place, and one can view papers and documents either in full text or with a limited preview, depending on the content provider and how much they want their content to be freely available. Google Scholar is one of the first places many researchers refer to when embarking on specific fact-finding.

|

|

Figure 13.1: Formulating queries for Google |

In some cases, it might also be relevant to search specifically for news items on different PGR-related issues, rather than websites in general. Strategies for doing this are discussed on the Google Books portal.

“Open” information resources: scholarly literature

The movement in scholarly publishing, known as open access, became much more prominent in the 1990s with the advent of the internet. It is a topic that in recent years has become the subject of much discussion among the academic community, funding agencies, government officials and publishers. "By 'open access' …we mean its free availability on the public internet, permitting any users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself” (Suber 2011).

Open-access scientific content is accessed in two primary ways: through open-access repositories (digital collections) where researchers archive or deposit their post-print, or via open-access journals and e-books. While open access was a term hardly heard of 16 years ago, a study carried out by Björk et al. (2010) revealed that 20% of peer-reviewed articles across all disciplines are now freely available over the web, and this figure will continue to grow as authors and their affiliated organizations begin to understand the benefits that open access can bring.

One such benefit is higher citations: open-access papers are more cited than papers that are behind a “payment wall” ( Hajjem and Harnad 2005; Harnad and Brody 2004; Swan 2010). Higher citations important for many universities or research organizations that want to improve their research impact and prestige. Yet, at the same time, content that is open access is often misunderstood, and at times the quality of the science published as open access is seen as somewhat inferior; however, as Swan (n.d.) succinctly states, “Open access is not self-publishing, nor a way to bypass peer-review and formal publication, nor is it a kind of second-class, cut-price publishing route. It is simply the means to make research results freely available online to the whole research community.” In fact, many open-access scientific journals are widely read and have impressive impact factors; the journal PLOS Biology has an impact factor of 12.469 (Thomson Reuters 2011)

There are numerous “open” information resources and platforms that are available on the internet for researchers working in plant genetic resources, where it is possible to access full-text research papers. Content is immediate, online and freely available without the use restrictions commonly imposed by publishers. Another major benefit open access brings is that it has removed the cost barrier for accessing scientific information, particularly for researchers and libraries in developing countries who cannot afford the cost of journal subscriptions. Major open-access resources include journal portals, institutional repositories and e-books. Details about selected resources are outlined in Table 13.2.

Table 13.2: Open-Information Resources: Scholarly Literature

This table outlines the major open-access websites and resources where it is possible to access the full text of research papers, documents and books. The main types of resources found in this table include journal gateways, virtual libraries and repositories. In most cases, content from these websites can be reused, disseminated and copied without requesting permission from the creator.

|

Resource Platform |

Type |

Facts and Features |

|

Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) |

Journal gateway |

|

|

HighWire Press |

Journal gateway |

|

|

Public Library of Science (PLOS) |

Journal gateway |

|

|

BioMed Central (BMC) |

Journal gateway |

|

|

Open J-Gate |

Journal gateway |

|

|

Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) |

Virtual library |

|

|

CGBooks on Google |

Virtual library |

|

|

OAISTER |

Virtual library |

|

|

Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) |

Search engine |

|

Social-media tools for researchers

On-line social-media platforms such as blogs, wikis and micro-blogging sites such as Twitter provide a quick, effective means of engaging with other researchers. They have rapidly changed the way science is communicated and disseminated in the last few years, allowing researchers to keep abreast of emerging trends and developments in their respective disciplines.

So what exactly are social media? They are “the use of web-based and mobile technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogue” (Wikipedia 2011a). Most social-media platforms encourage discussion, feedback and sharing of information. Tools such as Twitter, for example, allow a person participating in a conference to write short updates (called tweets) about what is being discussed in real time. The participant’s followers can keep abreast of the conference’s developments wherever they are located in the world, and they are able to respond and interact with the person providing the updates. This type of communication was unimaginable 16 years ago.

The uptake and use of these tools is increasing within the scientific and research community. Why are researchers increasingly using social-media tools? Gruzd and Staves (2011) and prior studies have highlighted three main benefits:

-

Researchers need to communicate with their peers, and social media allow them to do this regardless where they are located, at a low cost.

-

Social-media platforms provide researchers with the ability to create a community or network of like-minded scholars, which can facilitate and bring together people working on similar research.

-

Social media provide the opportunity to expand on ideas or research from the direct interaction between researchers and their readers.

In addition to Twitter, some of the more popular social-media platforms include wikis and blogs (see table 13.3 for specific links and more details about social-media platforms and tools). The wiki GRIN-Global is a good example of how researchers from different institutions in different locations in the field of plant genetic resources are able to collaborate and work together using social-media tools. Other social-media tools include forums (ScienceForums.Net) and platforms where one can upload and share scientific videos (SciVee), presentations (SlideShare) and images (Flickr). Only time will tell if these existing social-media platforms will be enhanced or even superseded by new technologies; however, the concept and value of “sharing ideas” is an integral part of human nature; consequently, it is difficult to think that social-media platforms will not continue to be part of our working and social domains for many years to come.

Table 13.3: Social Media Tools and Platforms

This table highlights social media websites that encourage scholarly discussion, feedback and sharing of information.

|

Resource name |

Coverage and Features |

|

Flickr |

|

|

Mixxt |

|

|

ResearchBlogging |

|

|

SciVee |

|

|

ScienceBlogs |

|

|

ScienceForums.net |

|

|

Slideshare/SlideBoom |

|

|

Twitter |

|

|

Wikis |

|

Bibliographical databases

Bibliographical databases are, and have always been, important tools for conducting research. With the advent of the internet, many of the bibliographic databases that were featured in the 1995 edition of the Technical Guidelines have remodelled themselves from standalone databases to web-based digital libraries. Often, these databases not only provide the full text to indexed and abstracted content, but also often provide the researcher with tools for analysis and are capable of carrying out federated searches across data silos. A federated search is an information-retrieval technology that allows the simultaneous search of multiple searchable resources. A user makes a single query request, which is distributed to the search engines participating in the federation. The federated search then aggregates the results that are received from the search engines for presentation to the user (Wikipedia 2011b).

These platforms are always in constant evolution and are consistently improving and extending content, search features and support tools. Table 13.4 provides a listing of the main bibliographic databases for agriculture and plant science, which will be useful to a researcher working in plant genetic resources.

Table 13.4: Agricultural Bibliographic Databases

This table highlights the main bibliographic databases that cover agriculture, PGR and the life sciences.

|

Resource name |

Coverage and Features |

|

AGRICOLA |

|

|

AGRIS |

|

|

CAB Abstracts/Plant Genetic Resources Abstracts (PGRA) |

|

|

FAO Corporate Document Repository |

|

|

Google Scholar |

|

|

ISI Web of Knowledge Access date: 07.07.2011 |

|

|

Mendeley Research Catalog |

|

|

MusaLit |

|

|

Science Citation Index (SCI) |

|

|

SciVerse |

|

|

Scirus |

|

|

Tropag and Rural |

|

|

World Wide Science.org |

|

Reference-management tools

With the huge amount of information and data available over the internet, researchers often struggle with how to manage the information they gather from databases and websites, as well as blogs and forums. Web-based reference-management systems can be the answer to this dilemma.

Reference-management software assists researchers and authors in managing the many bibliographic references they may have accumulated over time. The software is usually a database that allows for the creation of bibliographies and also acts as a personal online library. It has been around for many years, and with the advent of the internet, reference-management applications, like bibliographic databases, have evolved tremendously. From being databases installed on a stand-alone personal computer, these web-based platforms now have many features and tools. Apart from the traditional feature of generating bibliographies, today’s reference-management systems also possess social-networking elements, research catalogues, drag-and-drop features to reduce manual data inputting, and mobile applications for smart-phones and iPads. Some systems also allow users to save not only documents but also screenshots of web pages so that they have the ability to come back to the webpage at a later time. A growing number of reference-management systems are free over the web and can be of great benefit to researchers struggling to come to terms with the amount of information or data they have accumulated. Wikipedia (2011c) has a good article on reference management systems where it compares 29 systems (both free and proprietary). This information has been reproduced in part in table 13.5, which has a selection of the better known systems.

Table 13.5: Bibliographic Reference-Management Systems

Bibliographic reference-management systems are excellent tools for managing references and generating bibliographies and citations when writing research papers.

|

Software |

Developer |

Access |

Notes |

Operating systems |

Released |

|

Oversity Limited |

free |

|

Windows – Macintosh – Linux – BSD – Unix |

2004 |

|

|

Nature Publishing Group |

free |

|

Windows – Macintosh – Linux – BSD – Unix |

2004 |

|

|

Thomson Reuters |

cost |

has desktop and web account components |

Windows – Macintosh |

1998 |

|

|

Mendeley |

free & premium |

has desktop and web account components |

Windows – Macintosh – Linux |

2007 |

|

|

Thomson Reuters |

cost |

|

Windows |

1984 |

|

|

George Mason University |

free |

a Mozilla Firefox extension, so it can only be used with the Firefox browser |

Windows – Macintosh – Linux – BSD – Unix |

2006 |

Source: Wikipedia (2011c).

Future challenges/gaps/needs

In this chapter, we have looked at information tools and resources that can assist the researcher in the PGR domain. We have seen how a researcher can use many different platforms for resource discovery, and we have highlighted different formats/platforms that one can use to disseminate and generate content. All of these tools and resources will continue to evolve, change or be superseded by new technology, which ultimately means that researchers also need to keep abreast of how scientific information is generated and disseminated. Currently, a lot of focus has been given to mobile technology, where one can access information from smartphones or iPads and download applications that permit one to do an array of things, such as data analysis or creating tables. Tools such as these allow information to be generated and disseminated in a timely fashion; researchers do not need to wait until they are back at their desks. These tools have changed, and will continue to change, the way science is carried out, and it is to the researcher’s advantage to be aware of their availability and features.

As the scientific world moves more and more into the digital realm, one of the challenges researchers and their respective organizational libraries need to address is that a lot of scientific information is available only through subscription-based avenues. With the advent of digital information, a subscription often means that one is purchasing access to content but not the actual content, per se, as is the case with paper subscriptions, where one would put the journal on the shelf for as long as necessary. Company takeovers, for example, could affect access to digital information. Negotiations with publishers for perpetual access is necessary in order to retain access to content.

Another factor to contemplate is the gap in knowledge that exists between researchers from the South and those from the North. As Schisler (2011) states, “The digital divide is something we must not dismiss when considering the fact that anyone can now publish. The digital divide represents the socioeconomic difference among communities in their access to computers and the Internet. It is also about the required knowledge needed to use the hardware and software, the quality of these devices and connections, and the differences of literacy and technical skills between communities and countries…. When we think of the World Wide Web, as of today, it does not yet encompass the entire world. Many of the countries on the African continent, for example, have less than 5 Internet users per 100 inhabitants as opposed to the richer countries in the world that have over 50 Internet users per 100 inhabitants. We are seeing a small but decreasing gap in this divide, and this trend will continue.” Not everyone has the access to information that is taken for granted in many developed countries, and while the knowledge gap may be decreasing, it is still very evident in many developing countries. While addressing the question of how to overcome the complex issue of the digital divide is not the author’s intention, it is important to remind ourselves of the situation that is present today.

Conclusions

The last sixteen years has seen monumental changes in the way scholarly information is accessed, retrieved and re-used. As a result, the paradigm of scholarly publishing, communication and collaboration has changed dramatically since 1995 and it has provided the opportunity to bring the scientific community together in ways that before seemed impossible. This chapter has attempted to bring to the fore some of the most useful and pertinent resources for researchers working in the domain of plant genetic resources and to highlight some of the challenges, gaps and needs that could affect them or their respective organizations. The websites and research tools highlighted here will hopefully provide researchers with relevant and timely information, allow them to connect with their peers, and provide some respite from the “information overload” that one encounters when searching across the internet.

Back to list of chapters on collecting

References and further reading

Agichtein E, Gabrilovich E, Zha H. 2009. The social future of web search: modeling, exploiting, and searching collaboratively generated content. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 32(4):1–10. Available on-line (accessed 20 September 2011): http://sites.computer.org/debull/A09June/agichtein_ssm1.pdf .

Björk B-C, Welling P, Laakso M, Majlender P, Hedlund T, Guðnason G. 2010. Open access to the scientific journal literature: situation 2009. PLoS ONE 5(6): e11273/journal.pone.0011273. Available on-line (accessed 20 September 2011): www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0011273.

Gruzd A, Staves K. 2011. Trends in scholarly use of on-line social media. Academia.edu. Available on-line (accessed 20 September 2011): http://dal.academia.edu/AnatoliyGruzd/Papers/514997/Trends_in_scholarly_use_of_online_social_media.

Hajjem C, Harnad S, Gingras Y. 2005. Ten-year cross-disciplinary comparison of the growth of open access and how it increases research citation impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4):39–47. Available on-line (accessed 20 September 2011): http://sites.computer.org/debull/A05dec/hajjem.pdf.

Harnad S, Brody T. 2004. Comparing the impact of open access (OA) vs. non-OA articles in the same journals. D-Lib Magazine 10(6). Available on-line (accessed 20 September 2011): www.dlib.org/dlib/june04/harnad/06harnad.html.

Schisler M. 2011. The future of publishing – introduction. Online Encyclopedia, Net Industries. Available on-line (accessed 18 August 2011): http://encyclopedia.jrank.org/articles/pages/1088/The-Future-of-Publishing.html.

StatCounter. 2011. Top 5 search engines from Oct to Dec 10. StatCounter Global Stats. Available on-line (accessed 29 July 2011): http://gs.statcounter.com/#browser-ww-monthly-201010-201012.

Suber P. 2011. Budapest open access initiative: frequently asked questions. Earlham College, Richmond, IN, USA. Available on-line (accessed 29 July 2011): www.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/boaifaq.htm#openaccess.

Swan A. 2010. The open access citation advantage: studies and results to date. School of Electronics & Computer Science, University of Southampton, UK. Available on-line (accessed 20 September 2011): http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/18516/1/Citation_advantage_paper.docx.

Swan A. n.d. Open access: a briefing paper for research managers and administrators. EnablingOpenScholarship, Liege, Belgium. Available on-line (accessed 20 September 2011): www.openscholarship.org/upload/docs/application/pdf/2009-01/briefing_paper_open_access.pdf.

Thomson Reuters. 2011. Journal Citation Reports 2010. Thomson Reuters, New York. See http://thomsonreuters.com/products_services/science/science_products/a-z/journal_citation_reports/.

Wikipedia. 2011a. Social media. Available on-line (accessed 19 September 2011): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_media.

Wikipedia. 2011b. Federated search. Available on-line (accessed 25 August 2011): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federated_search.

Wikipedia. 2011c. Comparison of reference management software. Available on-line (accessed 28 July 2011: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_reference_management_software.

Comments

- No comments found

.jpg)

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest