Articles

Field bank (regeneration) guidelines for banana

Contributors to this page: Bioversity International, France (Nicolas Roux), Bioversity International, Ethiopia (Michael Bolton, Alexandra Jorge); CIRAD, France (Jean-Pierre Horry, Tomekpe Kodjo); IITA, Nigeria (Dominique Dumet).

Field bank for banana

When are field banks used

|

Banana field collection (photo: Bioversity) |

Many important varieties of field, horticultural and forestry species, including banana, are either difficult or impossible to conserve as seeds (i.e. no seeds are formed or if formed, the seeds are recalcitrant) or to reproduce vegetatively. Hence they can be conserved as growing plants in field genebanks or in vitro (in tissue culture or cryo banks).

Banana stored in field genebanks have a lower risk of loosing genetic integrity (due to genetic drift) if the mother plants are maintained for many years and are readily available for study and use. However, bananas maintained in field genebanks are considerably more exposed to physical risks (climate, diseases, pests) and costs are higher for storage (labour, inputs and space) than for in vitro genebanks. This balance must be considered before taking the decision to establish a field genebank for banana, if other options are also possible.

Advantages of field genebanks

- Material can be evaluated and characterized while being conserved.

- Genotypes that commonly produce variants can be more easily identified and rogued out in the field than in vitro.

- Lower risk of loosing genetic integrity.

- Easy access for research, utilization and distribution.

- Establishment and maintenance of field genebanks requires limited technology.

Disadvantages of field genebanks

- Materials are susceptible to pests, diseases, adverse weather, theft and vandalism.

- Field genebanks require large areas of land, but even then genetic diversity is likely to be restricted.

- High maintenance costs (labour, inputs and space).

- Slow multiplication of material for distribution.

|

View regeneration guidelines in full (in PDF) |

Regeneration guidelines for banana

Note: These guidelines refer specifically to the regeneration of banana in field collections and include information on the establishment of a new field collection.

For regeneration or rejuvenation of banana in in vitro collections click here.

The information on this page was extracted from:

Tomekpe K. and Fondi E. 2008. Regeneration guidelines: banana. In: Dulloo M.E., Thormann I., Jorge M.A. and Hanson J., editors. Crop specific regeneration guidelines [CD-ROM]. CGIAR System-wide Genetic Resource Programme, Rome, Italy. 9 pp.

Before reading the regeneration details for this crop, please read the general introduction that gives the general guidelines to follow, by clicking here.

Introduction

Banana and plantain (Musa spp. L.) are giant monocotyledonous perennial herbs that thrive in the humid and subhumid tropics of low- and mid-altitude areas. They originate primarily from South-East Asia, with secondary centres of diversity in West and Central Africa (Plantain subgroup) and the East African highlands (Lujugira subgroup). They belong to the genus Musa, which comprises more than 1000 varieties in four sections: Australimusa, Callimusa, Rhodochlamys and Eumusa (Simmonds and Shepherd 1955). Most cultivated Musa belong to the Eumusa section and produce fruits that are a major commodity in international trade but are even more important as starchy staples in local food economies of many developing countries.

Most cultivars are derived from two species: Musa acuminata Colla (A genome) and Musa balbisiana Colla (B genome). Most edible banana are triploids (2n = 3x = 33), although there are a few diploid cultivars and even fewer tetraploid cultivars.

Bananas and plantains are also classified according to use (dessert, cooking, beer or processing/fibre) or mode of preparation of the fruit. Sweet bananas are eaten fresh or unprocessed but most bananas, and particularly plantains with orange pulp, are cooked. Cultivated bananas and plantains are parthenocarpic and are propagated vegetatively.

They are conserved in field collections as actively growing plants or in vitro as proliferating tissue. Wild relatives (normally non-parthenocarpic) are conserved in the same way. Bananas and plantains consist of an underground organ (corm) that bears roots, suckers or shoots and a pseudostem with leaves. The corm or rhizome is the true stem. Suckers develop initially as swollen buds from lateral meristems at leaf bases on the corm. A sucker has different developmental stages (Stover and Simmonds 1987): peeper, sword sucker and maiden sucker. The recommended stage for regeneration is the sword sucker (a sucker that is 50-150 cm in height with lanceolate leaves) followed by the peeper (a large green bud that has just emerged above ground). Among the followers or daughter plants, a sucker or ratoon is selected to succeed the mother plant. A group of suckers from a single parent is referred to as a stool or mat. A crop cycle is the time between planting and fruit harvest on the same mat. The second harvest from the mat is called the first ratoon crop (Gowen 1995).

Description is an important step in regeneration: |

Choice of environment and planting

Climatic conditions

Banana grows well:

- In humid tropical lowlands between latitudes 20°N and 20°S.

- Between 100 m and 500 m altitude.

- Above 19°C mean minimum temperature (optimum average temperature is 27°C).

- In areas with >100 mm monthly rainfall (Robinson and de Villiers 2007).

However, banana can grow in a much wider range of climates within the tropics, with site selection mainly limited by soil type and rainfall.

Planting season

Planting can be done all year round if there is enough moisture. Planting should be done at the beginning of the rainy season.

Preparation for regeneration

When to regenerate

Regenerate field collections every four years to restore collections, as accumulated diseases and pests reduce plant vigour. Regeneration also allows maintenance (re-alignment) of planting pattern and optimal density since successor plants of banana emerge at variable distances away from the parent stand.

Sword sucker obtained from parent plant for regeneration (photo: Emmanuel Fondi) |

Field selection and preparation

- Banana field collections are maintained indefinitely. It is necessary to have twice as much space as occupied by the collection (i.e. if a collection of 700 accessions occupies 3 ha, you need to have 6 ha available) for fallowing which is essential for proper growth of accessions.

- The best soils for banana are deep, well-drained fertile loams with high water-holding capacity and organic matter content (Purseglove 1972).

- Select fields that were not under banana during the previous two years or that were planted to a non-host crop like pineapple.

- Choose soils with adequate drainage and where water-logging is not a problem.

Method of regeneration

Both parthenocarpic edible bananas and their wild relatives are regenerated vegetatively. In this way the genetic identity remains unchanged from one cycle to the next. To safeguard the entire biodiversity, it is necessary to regenerate all the accessions.

Planting layout, density and distance

The planting layout of a banana collection should take account of the genomic constitution of the varieties and the use types of the accessions. Make a field plan (electronic and hard copy). See sample plan below.

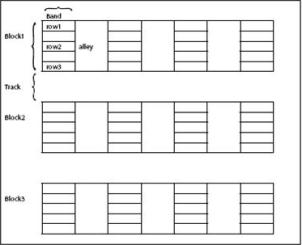

Divide the site into main blocks separated by 6-m-wide tracks. Blocks should correspond to the genomic group or the main subgroup, e.g. plantain. Assign block names and then:

Parent plant with suckers to be used for regeneration. (photo: Emmanuel Fondi) |

- Further divide the blocks into bands directed at right angles to the blocks. The bands correspond to the different subgroups.

- Plant in single rows, with five plants per row.

- Use a plant spacing of 3 m between rows and 2 m within each row.

Source of planting material

- The best planting materials are sword or maiden suckers collected from the accession to be regenerated (see photo on the right), which do not develop broad leaves until they are more than 1 m high.

Selection of planting material

- Choose plants at flowering or at the end of the growing season.

- Plants should be free of undesirable variations in the cultivar characteristics.

The following diseases must be avoided: Moko disease due to Ralstonia solanacearum Smith, phylotype II, Xanthomonas wilt (bacteria wilt) caused by Xanthomonas vasicola pv. musacearum, Panama disease (Race 1 and 2) and other vegetative compatibility groups (VGCs) of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, Banana bunchy top virus (BBTV), Banana bract mosaic virus (BBrMV).

Other pests and diseases, especially nematodes, weevils and other viral and bacterial diseases, should be absent or have a low prevalence in the field from which planting material is extracted. Monitor by regular field inspections.

Preparing planting material and method

- Suckers removed from the mother plant must be pared in the field to remove all the roots and diseased tissue before being transported (see photo below). Remove any suspect part of a different colour. Discard sucker if darkened galleries, dead or discoloured areas or other damage make up one quarter to one third of the sucker.

Paring of sucker to eliminate soil-born pests and diseases (photo: Emmanuel Fondi) |

- Disinfect the machete after each sucker in a 5% sodium hypochlorite solution or a 20% iodine solution to avoid spreading disease (bacterial wilt and Fusarium).

- Cut the pseudostem in cross section 10-15 cm above the corm to examine for any off-coloured rings, brownish spots or off-coloured liquid. Eliminate suckers or corms showing these characteristics.

- To prevent re-infection with banana weevil borer once sucker paring is complete, transport the suckers immediately to a site distant from any banana fields to limit the risk of weevils laying eggs in the planting material.

- Place identification tags on suckers and give particular care to the identity of suckers from each accession before removing them from the field.

- When the suckers are to be planted directly or into a multiplication plot, immerse them in hot water (30 seconds in boiling water or 20 minutes in water at 50°C) to kill weevil borer eggs and nematodes, if needed.

- Plant suckers directly in loose soil using hoes or spades if deep ploughing has been done.

- If deep ploughing is not done, plant suckers in square holes with sides of 40 cm and depth of 40 cm.

It is indicated to plant the suckers at once after their pulling up and treatment and if it is not possible, one or a few days afterwards suckers can however be stored for several weeks in a shaded dry area until planting is completed.

Labelling

- Place metallic identification plates at the head of rows to identify accessions (see photo below).

Metallic plate to identify accession (photo: Emmanuel Fondi) |

Crop management

Fertilization

Fertilizer practices vary widely according to climate, cultivar, yield level, soil fertility and production system. Before planting, take a composite soil sample from each block or from each soil type change. Analyse the sample to determine soil pH and micronutrient levels. This should provide a reliable recommendation for pre-planting application of lime (dolomitic or calcitic), K and P. The normal pH range is 5.8 to 6.5. Below this, lime application is required. Top dressing with N and K is recommended according to the expected yield level and results of soil analysis.

Weed management

Weeds can be manually or chemically controlled.

- Apply a post-emergent, non-selective systemic herbicide (e.g. glyphosate) two weeks before planting. Clear manually once a month during early stages of crop growth.

- Apply herbicide when the plants have grown tall enough to permit direct spraying, but apply with care as the banana plants are very sensitive to herbicides.

Mulching

Mulch with organic matter to reduce evapotranspiration and to increase the organic matter content of the soil. Elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum Schumach.) is a popular mulch in Central Africa, particularly for plantains and diploid bananas. It is rich in potassium and improves soil fertility.

Pruning and de-suckering

- Prune once a month to eliminate withered leaves and reduce leaf disease pressure.

- De-sucker plants regularly to maintain a single successor sucker at a time. De-suckering should be carried out in such a way as to maintain the initial planting layout.

Irrigation

Irrigation is required during the dry season to keep the plants vigorous.

Common pests and diseases

Major pests of banana include nematodes, banana weevil borer, tomato semi-looper (Chrysodeixis acuta) and thrips.

Major diseases include Panama wilt (Fusarium oxysporum), bacterial wilt (Xanthomonas wilt), Erwinia rhizome rot, black and yellow Sigatoka (Mycosphaerella), cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), banana bunchy top virus (BBTV) and banana streak virus (BSV). Do not distribute accessions contaminated with viruses.

Pest and disease control

- Proper cultural practices, such as fallowing, balanced nutrition and weed control, help keep disease pressure at a minimum.

- The main pesticides required are insecticides and nematicides; about two applications are required per year.

- Sigatoka diseases are controlled by pruning infected leaves and/or applying fungicides. Viral diseases are major threats to a collection and are controlled by prevention, principally by controlling the source and the quality of material introduced in to the collection. Infected plants should be uprooted and destroyed as soon as they are identified.

Harvesting

The regeneration of bananas does not involve seeds. At maturity (when first ripe fruit appears on bunch), description is carried out and the fruits taken for consumption in the case of parthenocarpic edible banana types. For wild types, the entire plant is cut down and placed in the interline space.

Regeneration of wild banana

The regeneration procedures for wild banana should be the same as for edible types.

Monitoring accession identity

Comparisons with passport or morphological data

Accessions are characterized using minimum descriptor forms adapted from‘Descriptors for bananas’ (IPGRI/INIBAP, CIRAD 1996). Typical reference materials are photos and description forms.

Reference sources for comparison include Musalogue (Daniells et al. 2001) and the Musa Germplasm Information System (MGIS) database.

Compare the following major traits in characterization data:

- General plant appearance.

- Bunch characteristics.

- Male bud characteristics.

An accession is declared true to type (TTT) if its traits match those of the known reference.

In cases where they do not match with the reference, it is declared either as miss-labelled (ML) or off type (OT). If it is mislabelled, its true identity is sought; whereas if declared off-type, it is destroyed and the right accession re-introduced in to the collection.

Documentation of information during regeneration

The following information should be collected during regeneration:

- Regeneration site name and map/GPS reference.

- Name of collaborator.

- Field/plot reference.

- Accession number, accession code in the institute, ITC code; population identification.

- Source of suckers.

- Abnormalities on the mother plant and sucker.

- Generation or previous multiplication or regeneration (if generation is not known).

- Preparation of planting materials (pre-treatments).

- Planting date and density.

- Field layout used.

- Field management details (watering, fertilizer, weeding, pest and disease control, stresses recorded, others).

- Environmental conditions (altitude, precipitation, soil type, others).

- Emergence in the field (number of plants germinated).

- Number of plants established.

- Days from planting to flowering.

- Agronomic evaluation; agromorphological traits recorded.

- Comparisons with reference materials (record any identification numbers or references of any samples taken from this regeneration plot).

- Others.

References and further reading

Daniells J, Jenny C, Karamura D, Tomekpe K. 2001. Musalogue: Diversity in the genus Musa. IPGRI/INIBAP/CTA, Rome, Italy. Available from: http://www.bioversityinternational.org/publications/publications/publication/issue/imusailogue_diversity_in_the_genus_imusai.html (16 MB). Date accessed: 23 March 2010.

IPGRI, INIBAP, CIRAD. 1996. Descriptors for Banana (Musa spp.). IPGRI, Rome, Italy; INIBAP, Montpellier, France; CIRAD, France. 55 pp. Available here.

Lassoudiere A. 2007. Le bananier et sa culture. Editions Quae, Versail es Cedex, France. 383 pp.

Purseglove JW. 1972. Tropical Crops. Monocotyledons. Vol. 2. Longman, London, UK.

Robinson JC, de Villiers EA. 2007. The cultivation of banana. ARC-Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops, Nelspruit, South Africa/Du Roi Laboratory, Letsitele, South Africa. 258 pp.

Simmonds, N.W. and Shepherd, K. 1955. The taxonomy and origins of the cultivated bananas. Journal of the Linnean Society (Bot.), 55(359), p. 302-312 Abstract available from: www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/119777761/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0. Date accessed: 23 March 2010.

Stover RH, Simmonds NW. 1987. Bananas. Longman Scientific and Technical, New York, USA. 468 pp.

Swennen, R. 1990. Plantain Cultivation under West African Conditions: A Reference Manual. IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria. 24p.

Acknowledgements

These guidelines have been peer reviewed by Sebastião de Oliveira e Silva, Centro Nacional de Pesquisa de Mandioca e Fruticultura Tropical (CNPMF), Brazil; Wayne Hancock, Bioversity International, Ethiopia; and Jeff Daniells, Department of Primary Industries & Fisheries, Queensland, Australia.

Comments

- No comments found

Leave your comments

Post comment as a guest