CGKB News and events Characterization

Characterization of cultivated rice, wild rice and related genera

Mature open panicle (photo:IRRI) |

Contributors to this page: T.T. Chang Genetic Resources Centre-IRRI, Los Baños, Philippines (Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton, Ken McNally, Flora de Guzman, Renato Reaño, Soccie Almazan, Adelaida Alcantara, Elizabeth Naredo); WARDA, Cotonou, Benin (Ines Sánchez); UPLB-University of the Philippines at Los Baños (Teresita Borromeo).

|

Contents: |

Planting and cultural practices for characterization

For details on cultivated rice, click here.

For details on wild rice and related genera, click here.

Morphological descriptors for characterization

See list for rice descriptors developed by Bioversity International, IRRI and AfricaRice, (2007) and key access and utilization descriptors for rice genetic resources developed by Bioversity International and International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) (2009).

Pictures for characterization

Sufficient detail should be captured in images to taxonomically identify the plant and demonstrate the traits that show variation.

From paddy (left) to brown rice (center) to polished rice (right) (photos: IRRI) |

- Take images for character(s) which may be difficult to describe verbally.

- Intact inflorescence.

- Whole grain as harvested (‘paddy’).

- De-hulled unpolished caryopsis (‘brown rice’).

- Polished rice.

- Store in a database file linked to other characterization data.

Herbarium samples for characterization

Use only for wild rice and related genera, where it is useful to have references.

- Sufficient detail should be captured to taxonomically identify the plant and demonstrate the traits that show variation.

- Take and store vouchers for future reference and taxonomic verification.

- Collect plants with leaves, flower spikes and seeds as well as roots.

- Spread plants open before pressing.

Molecular descriptors for characterization

Prior/current:

- Selected SSR markers with allelic controls (protocols for SSR marker technology are established; however, accurate scoring across diverse germplasm presents significant difficulties).

Current/near future:

- SNP genotyping platforms (SNPs arrays have been established, removing issues with scoring quality, and are replacing SSRs as the preferred technology).

Cytological characterization

- Not useful for cultivated rice, which are all diploid with AA genome (in contrast with wild rice species which have a range of genomes).

- Wild rice species are all either diploid (2n=24) or tetraploid (2n=48). Chromosome counts are a valuable aid to taxonomic identification.

- Wild rice species have chromosomes with recognizably different morphologies, classified as AA, BB, ..., KK.

Nutritional traits for characterization

- See list for rice descriptors developed by Bioversity International, IRRI and AfricaRice, 2007.

Recording information during characterization

- See list for rice descriptors developed by Bioversity International, IRRI and AfricaRice, 2007.

|

|

|

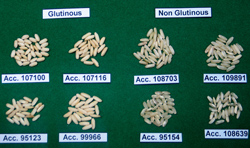

Grain diversity: grains from Laos |

Showing the different stages of maturity of black caryopsis (photo: IRRI) |

References and further reading

Bioversity International, IRRI. 2009. Key access and utilization descriptors for rice genetic resources. Bioversity International, Rome, Italy; International Rice Research Institute, Philippines. Available here.

Bioversity International, IRRI and WARDA. 2007. Descriptors for wild and cultivated rice (Oryza spp.). Bioversity International, Rome, Italy; International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippines; WARDA, Africa Rice Center, Cotonou, Benin. Available here. (1.2 MB)

Borromeo TH, Sanchez PL, Vaughan DA. 1994. Wild rices of the

Chakravarthi BK, Naravaneni R, 2006. SSR marker based DNA fingerprinting and diversity study in rice (Oryza sativa L.) [online]. Available from: http://ajol.info/index.php/ajb/article/viewFile/42772/26341. Date accessed: 10 July 2013.

Chang TT, Vaughan DA.1989. Conservation and potentials of rice genetic resources. In: Bajaj YFS, editor. Biotechnology in agriculture and forestry.

Hanson J. 1985. Practical Manuals for Genebanks: Procedures for handling seeds in genebanks. IBPGR, Rome, Italy. HTML version available from: http://www2.bioversityinternational.org/publications/Web_version/188/. Date accessed: 10 July 2013.

IRRI. 2000. Manual of operations and procedures of the International Rice Genebank. Genetic

Korzun V. Molecular markers and their application in cereals breeding [online]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/biotech/docs/Korzun.pdf. Date accessed: 10 July 2013.

Lu BR. 1999. Taxonomy of the genus Oryza (Poaceae): Historical perspective and current status. IRRN 24.3. IRRI, Los Baños, Laguna.

Micro satellite markers [online]. Available from: http://www.gramene.org/markers/microsat/. Date accessed: 10 July 2013.

McNally KL, Bruskiewich R, Mackill D, Buell RC, Leach JE and Leung H. 2006. Sequencing multiple and diverse rice varieties. Connecting whole-genome variation with phenotypes. Plant Physiology 141, 26-31. Available from: http://www.plantphysiol.org/content/141/1/26.full. Date accessed: 15 July 2013.

Naredo MEB, Juliano AB, Lu BR, de Guzman FC, Jackson MT. 1998. Responses to seed dormancy breaking treatments in rice species (Oryza L). Seed Science and Technology 26:675-689.

Rao NK, Jackson MT. 1996a. Seed longevity of rice cultivars and strategies for their conservation in genebanks. Annals of Botany 77:251–260.

Rao NK, Jackson MT. 1996b. Seed production environment and storage longevity of japonica rices (Oryza sativa L.). Seed Science Research 6:17–21.

Rao NK, Jackson MT. 1996c. Effect of sowing date and harvest time on longevity of rice seeds. Seed Science Research 7:13–20.

Rao NK, Hanson J, Dulloo ME, Ghosh K, Nowel D, Larinde M. 2006. Manual of seed handling in genebanks. Handbooks for Genebanks No. 8. Bioversity International, Rome, Italy. Available in English (1.5 MB), Spanish (1.4 MB) and French (1.9 MB).

Reaño R, Pham JL. 1998. Does cross-pollination between accessions occur during seed regeneration at the International Rice Genebank. International Rice Research Notes 23(3):5-6.

Reed BM, Engelmann F, Dulloo ME, Engels JMM. 2004. Technical guidelines for the management of field and in vitro germplasm collections. Handbook for Genebanks No. 7. IPGRI, Rome, Italy. Available here.

Sackville-Hamilton NRS, Chorlton KH. 1997. Regeneration of accessions in seed collections: a decision guide. Handbook for Genebanks No. 5. IPGRI, Rome, Italy. Available here.

Sarao NK, Vikal Y, Singh K, Joshi MA, Sharma RC. 2009. SSR marker-based DNA fingerprinting and cultivar identification of rice (Oryza sativa L.) in Punjab state of India.

Tateoka T. 1962a. Taxonomic studies of Oryza I. O. latifolia complex. Bot. Mag. Tokyo 75:418-427.

Tateoka T. 1962b. Taxonomic studies of Oryza II. Several species complexes. Bot. Mag. Tokyo. 75:455-461.

Tateoka T. 1963. Taxonomic studies of Oryza III. Key to the species and their enumeration. Bot. Mag. Tokyo. 76:166-173.

van Soest LJM. 1990. Plant Genetic Resources: Safe for the future in genebanks. Impact of Science on Society 158:107-120.

Vaughan DA. 1989. The genus Oryza L. Current status of taxonomy. IRRI Research Paper Series 138,

Vaughan DA, Sitch LA. 1991. Gene flow from the jungle to farmers. Bioscience, Vol. 41(1):22-28.

Vaughan DA. 1992. The wild relatives of rice: A genetic resources handbook. IRRI,

Vaughan DA, Chang TT. 1992. In situ conservation of rice genetic resources. Economic Botany 46(4):368-383.

Vaughan DA, Morishima H, Kadowaki K. 2003. Diversity in the Oryza genus. Current Opinion 6:139-146.

Cultural practices for characterization of cultivated rice

Contributors to this page: T.T. Chang Genetic Resources Centre-IRRI, Los Baños, Philippines (Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton, Ken McNally, Flora de Guzman, Renato Reaño, Soccie Almazan, Adelaida Alcantara, Elizabeth Naredo); WARDA, Cotonou, Benin (Ines Sánchez); UPLB-University of the Philippines at Los Baños (Teresita Borromeo).

Planting and cultural practices

Environment

Characterization trial of rice (photo: IRRI) |

- For large diverse collections encompassing varieties from different ecosystems, use irrigated lowland with good drainage (this provides a single common environment suitable for growing and comparing almost all varieties, including upland, lowland and deep water varieties, regardless of their normal ecosystem and adaptation).

- For collections targeted to particular ecosystems, use the corresponding ecosystem (matching the ecosystem to the target provides more realistic characterization of varieties adapted to that ecosystem).

Note: In rice agriculture, the terms ‘upland’ and ‘lowland’ conventionally refer to the type of cultivation, not to the elevation of the land. Thus it is possible (and common) to have ‘upland’ rice in the lowlands and ‘lowland’ rice in the uplands.

‘Upland’ = on sloping land never inundated in water.

‘Lowland’ = on level ground periodically inundated, by rainfall or by irrigation water, to control weeds.

Soil type

- Silt clay to clay loam (best for lowland rice cultivation).

Rainfall

- Medium-high, or irrigate (rice does not grow well under drought; it needs either abundant rainfall or effective irrigation).

Season

- As appropriate to rice cultivation in the region.

- In tropical areas with two cropping seasons per year, select one season per year for characterization: usually the season that starts while days are growing longer.

- Long-duration varieties will extend into the second cropping season (using one fixed season each year improves consistency between trials.

- Some rice varieties are short-day photoperiod sensitive.

- In tropical latitudes higher than about 10°, the sensitivity to photoperiod (a key trait) can be tentatively characterized without multiple treatments by planting as the days are growing longer (e.g. in April-May in the northern hemisphere, October-November in the southern hemisphere); photoperiod sensitive accessions then remain vegetative for a prolonged period until the days shorten again. However, this does not distinguish between photoperiod-sensitive and long-duration photoperiod-insensitive varieties).

Plot size

- 5 m2 - 3 rows 5 m long (minimum plot size providing one row for sampling and one border row on each side).

Sampling area/border area

- Sampling area - one central row.

- Border area - one row on the edge of each plot, i.e. two border rows between successive sampled rows (minimum area good enough to record required traits at minimum maintenance cost).

Plant density

- Single seedling per hill, 30 x 30 cm between hills (use wider spacing than common agricultural practice for improved recording of tillering ability).

Replications

- Normally unreplicated entries, control varieties are replicated every 150 entries (replication of only control varieties is sufficient for normal assessment of highly heritable morpho-agronomic traits; more economical and thus allowing the screening of more accessions).

- For special purpose characterization for more rigorous statistical analysis, full replication is necessary.

Standard check cultivars

- For large diverse collections spanning all types, use up to six control varieties from the main taxonomic variety groups (glaberrima, indica, japonica, aus) and morpho-agronomic groups (glutinous, semi-dwarf).

- For smaller collections targeted at a particular ecosystem or environment, use a smaller number of check cultivars as appropriate for the target ecosystem and environment.

Frequency of standard checks

- Plant the full set of selected check varieties every 150 entries (this is the best practices considering the number of entries being handled and randomly scattered across the entire size of the field).

Time of day for data collection

- Field data are best collected in the morning (best time for consistent characterization of traits such as flowering that vary through and are most apparent in the morning. Best time also for the effectiveness of the observer).

- Post-harvest data can be taken any time, but for efficient use of time, good practice is to alternate field work in the morning with post-harvest characterization indoors in the afternoon.

Consult the general rice characterization page for information about descriptors, or recording of information during characterization.

References and further reading

Hanson J. 1985. Practical Manuals for Genebanks: Procedures for handling seeds in genebanks. IBPGR,

Rao NK, Jackson MT. 1996a. Seed longevity of rice cultivars and strategies for their conservation in genebanks. Annals of Botany 77:251–260.

Rao NK, Jackson MT. 1996b. Seed production environment and storage longevity of japonica rices (Oryza sativa L.). Seed Science Research 6:17–21.

Rao NK, Jackson MT. 1996c. Effect of sowing date and harvest time on longevity of rice seeds. Seed Science Research 7:13–20.

Rao NK, Hanson J, Dulloo ME, Ghosh K, Nowel D, Larinde M. 2006. Manual of seed handling in genebanks. Handbooks for Genebanks No. 8. Bioversity International, Rome, Italy. Available in English (1.5 MB), Spanish (1.4 MB) and French (1.9 MB).

Reaño R, Pham JL. 1998. Does cross-pollination between accessions occur during seed regeneration at the International Rice Genebank? International Rice Research Notes 23(3):5–6.

Reed BM, Engelmann F, Dulloo ME, Engels JMM. 2004. Technical guidelines for the management of field and in vitro germplasm collections. Handbook for Genebanks No. 7. IPGRI, Rome, Italy. Available here.

Sackville-Hamilton NRS, Chorlton KH. 1997. Regeneration of accessions in seed collections: a decision guide. Handbook for Genebanks No. 5. IPGRI, Rome, Italy. Available here.

Van Soest LJM. 1990. Plant Genetic Resources: Safe for the future in genebanks. Impact of Science on Society 158:107-120.

Cultural practices for characterization of wild rice

Contributors to this page: T.T. Chang Genetic Resources Centre-IRRI, Los Baños, Philippines (Ruaraidh Sackville Hamilton, Ken McNally, Flora de Guzman, Renato Reaño, Soccie Almazan, Adelaida Alcantara, Elizabeth Naredo); WARDA, Cotonou, Benin (Ines Sánchez); UPLB-University of the Philippines at Los Baños (Teresita Borromeo).

Wild rice is best characterized during the seed regeneration process. So the following cultural practices are the same as the regeneration guidelines of wild rice.

Choice of environment and planting season

Climatic conditions

- Most accessions of wild rice require different cultural management practices for seed increase compared to those of the cultivated rices.

- During plant growth it is necessary to simulate the habitat/growing environment of the original collection sites of each of the species to promote flowering.

- Cultural practices should be integrated with intensive monitoring of pests and diseases.

- Several species such as O. meyeriana, O. granulata, O. ridleyi and O. longiglumis grow better under partial shade, while others like some of the O. sativa complex grow well under full sunlight. These are usualy found in wet or seasonally wet habitats.

- Grow the plants in 30 cm wide-mouthed pots without holes, so they can be placed in different levels of shade in the screen house.

Planting season

- Most of them are strongly photoperiod-sensitive so that the best time to grow them is during a season with short daylength to induce panicle initiation.

- Planting of wild rice should be planned so that plants reach the reproductive stage when the shortest day length occur. In the Philippines they should be planted during the wet season (June) so that they have the reproductive stage during the shortest days that occur in December.

Preparation for regeneration

When to regenerate

The frequency of regeneration is determined by the quantity of seeds stocks left at the genebank.

The selection of material for planting depends upon the available space in the screen house facility as space is usualy a limiting factor.

- When stocks are insufficient.

- When viability reachs low or zero values.

- When seed samples are infected.

- When morphological characterization is scheduled.

- When there are small seed quantities from newly received samples.

- When there are highly heterogenous samples.

Propagation method

- Wild taxa are readily propagated by seeds.

- Some species like O. schlechteri are maintaned asexually through its vegetative stolons.

- O. longistaminata is maintained asexually with its rhizomes.

- Other perennial species can also be propagated by separating tillers of its vegetative crown.

Breeding system

- Rice is self-pollinated but some wild species have some degree of out-crossing.

Isolation

- Artificial barriers like net bags or glassine bags should be used to control inter-accession pollination.

- Net fencing using net curtains should be constructed to separate species like O. longistaminata.

- Pots should be planted with alternating species of different complexes.

Pre-treatments

Wild species are known to have stronger dormancy than the cultivated species. They may require one or a combination of dormancy breaking treatments including heat treatment, dehulling, exposure to alternating temperatures and, in some cases, chemical treatments.

Heat treatment

- In most species, heat treatment at 50°C for 10-14 days, followed by acclimatization at room temperature for 5-7 days is done before hull removal to promote germination of newly harvested seeds.

- If seeds are withdrawn from storage facility, allow 2-3 days for the seeds to adjust to room temperature before applying heat treatment.

- For species belonging to O. sativa complex, exposure to alternating temperatures of 45ºC and 30ºC (45/30) is generally effective in breaking dormancy. It is recommended, however, that the seeds be transferred to 30ºC after radicle emergence to achieve maximum seedling growth.

Dehulling

- Seed hull removal is recommended for most species to effectively break seed dormancy, but it is labour intensive and demands great care as not to damage the seed embryo.

- Treat dehulled seeds with a fungicidal suspension and wash thoroughly.

- Germinate on moist filter paper in petri dishes and place inside a germinator with 30°C and 100% RH.

Chemical treatment

- For some species, chemical treatment and/or dry heat method are more applicable and efficient when handling a large number of samples.

Method of regeneration

Sowing method

- Plant the germinated seeds 1-2 cm apart, in a seed box containing moist, fine, clean (preferably sterilized) soil mixed well with appropriate amount of ammonium sulfate.

- Apply a granular insecticide (e.g. Furadan) 3-4 days after planting to protect the seedlings from ants and other insects.

- Water the seedlings carefully with a fine spray, and grown them under partial shade until a week before transplanting.

Transplanting

- Transplant the seedlings 30 days after sowing to water-tight pots with good quality soil mixed with about 5 g of complete fertilizer.

- Maintain the water level to at least 1-2 cm depth.

- A granular insecticide (e.g. Carbofuran) should be applied 7 and 14 days after transplant to protect the plants against hoppers and defoliators.

Planting layout, density and distance

- Use 5-10 pots for highly heterogeneos populations with low seed-set samples.

- Otherwise, 3-4 pots are enough to produce seeds for storage.

- Pots should be laid out at least 100 cm apart to provide sufficient ventilation between plants and enough space for plant management, but preventing from constant humid conditions that are conducive to disease development.

- When pure lines are to be developed, only one plant per pot should be maintained and spaced widely, preferably alternating species of diferent complexes.

- If a bulk population is required, 2-3 seedlings per pot should be transplanted and all plants maintained.

Planting conditions

- For species of the O. meyeriana complex, the seedlings should be transplanted into pots with light soil and good internal drainage to prevent water logging as they thrive best in mesophytic conditions.

- For the highly stoloniferous species, such as O. schlechteri and some related genera like Luziola, Leersia, and Hygroryza, a modified flat bed should be constructed and used for growing and maintaining a single accession.

- All species of the genus Oryza grow well under full sunlight except members of the O. meyeriana complex and O. ridleyi complexes which are best maintained in partial shade.

- Accessions difficult to germinate should be cultured on agar, and seedlings raised in culture solution in the Phytoron facility, where growth environment can be modified, before transfer and reared in the screen house.

- For the highly photo-sensitive species like O.schlechteri, continued modifications of conditions for flower induction may be needed.

Different varieties of rice being grown inside an IRRI green house (photo: IRRI) |

Crop management

Fertilization

- Top dressing is recommended at 30 and 45 days after transplant with 5 g ammonium sulfate per pot.

- For O. meyeriana complex, 2 g of ammonium sulfate should be applied weekly during three weeks, 30 days after transplant.

Irrigation

- Plants should be watered daily, maintaining at least 1-2 cm depth.

Pest and disease control

- Plant health should be monitored closely and regularly, with seed health unit inspectors, as well as representatives from governmental health offices.

- Appropriate and intensive control measures should be applied to specific pest and diseases once symptoms appear.

- Spray liquid insecticides (emulsifiable concentrate and/or wettable powder) when need arises.

- Spraying soap detergent can help to control some small sucking insect pests.

- Maintaining the cleanliness of plants also helps preventing the spread of diseases.

- Infected/diseased plants should be rouged and eliminated.

Thinning

- When purelines are to be developed, only one plant per pot should be maintained and spaced widely, preferably alternating species of different complexes.

- If a bulk population of seeds is required, 2-3 seedlings per pot should be transplanted and all the plants should be maintained.

Harvesting

Panicle bagging

- At the late vegetative stage, (about 60 days after transplant) the tillers should be tied loosely with for example an abaca twine to a bamboo stake (5 cm x 2 m) to prevent plants from encroaching from one pot to another, at the late reproductive stage, to facilitate panicle bagging.

- Panicle bagging is necessary for handling wild rices to minimize outcrossing, to prevent seed loss due to shattering and to prevent mixtures at harvesting.

- Panicles should be bagged a week after full panicle emergence using nylon net bags, which provide ample ventilation to facilitate anther dehiscence and prevent mold formation on glumes.

- For species with shorter panicles, glassine bags are a good substitute.

- The net bag should be pinned to the bamboo pole.

- Prior to bagging, labels should be prepared using shipping tags written with plot number and date of bagging with indelible ink.

- The labels must be attached inside the net bags.

Rice being grown inside an IRRI screen house. Notice the bagged panicles (photo: IRRI) |

Panicle harvesting

- The panicles should be harvested 30 days after bagging or when most of the seeds have shattered.

- If sufficient seeds are obtained, the plants should be discarded and disposed through burning.

- However, for species with low seed set like O. rufipogon and O. longistaminata, the plants should be ratooned by cutting about 20-25 cm from the culms base, a little amount of ammonium sulfate should be applied and plants should be maintained until the next flowering to maximize seed production.

Post harvest management

Seed processing

- After harvesting, the panicles should be dried slowly to 6% moisture content and kept inside a drying room (15oC and 15% RH) for about 2-4 weeks.

- Seeds should be authenticated and cross-referenced against the seedfile before carefully hand threshing and cleaning.

- A 20 grain sample should be taken for seed viability testing.

Disposal of contaminated material

To ensure plants do not spread by seeds or rhizomes, specific measures should be followed:

- Carry out the seed multiplication of all wild rices inside the screen house in pots.

- Quarantine measures should be strictly followed to further minimize dissemination of seeds or rhizomes.

- Designate a disposal area (a pit about 3-4 m deep from the surface ground) for burying discarded and burnt samples to properly control spread of seeds or rhizomes.

- Provide a modified incinerator or burning facility to accommodate burning activities especially during the rainy season.

- Cover all drainage canals inside the screen house with fine-mesh screens to further control dissemination of seeds through water.

- Waste material from the canals should be regularly hauled, burned and buried.

- If sufficient seeds are obtained, old plants should be discarded, burned and buried into the pit.

- Excess planting material (seeds, seedlings, rattooned tillers) should be collected, burned and buried after seeding, transplanting and/or replanting.

- Discarded soil used in growing should be treated with herbicide and buried in the designated area.

- Before filling up all the discarded material, the disposal area should be treated with a non-selective herbicide (e.g. glyphosate).

- Spray with herbicides to kill persistent species.

- Screen house staff should be advised to change their working clothes to minimize dispersal of seeds when they leave.

- Hand threshing and seed cleaning should be done in a specified room in the Seed Processing Area of the genebank.

- All dried leaves/straws, unfilled grains, mixtures and off-types must be collected, burned and buried.

- The access to screen houses should be regulated depending on the nature/importance of the visit.

Recording information

Consult the general rice characterization page for information about descriptors, or recording of information during characterization.

References and further reading

Borromeo TH, Sanchez PL, Vaughan DA. 1994. Wild rices of the Philippines. Philippine Rice Research Institute, Maligaya, Nueva Ecija, Philippines.

Chang TT, Vaughan DA.1989. Conservation and potentials of rice genetic resources. In: Bajaj YFS, editor. Biotechnology in agriculture and forestry. Springer Verlag, Berlin.

Hanson J. 1985. Practical Manuals for Genebanks: Procedures for handling seeds in genebanks. IBPGR, Rome, Italy. HTML version available from: http://www2.bioversityinternational.org/publications/Web_version/188/. Date accessed: 10 June 2010.

Lu BR. 1999. Taxonomy of the genus Oryza (Poaceae): Historical perspective and current status. IRRN 24.3. IRRI, Los Baños, Laguna.

Manual of operations and procedures of the International Rice Genebank. 2000. Genetic Resources Center, IRRI. Available here.

Naredo MEB, Juliano AB, Lu BR, de Guzman FC, Jackson MT. 1998. Responses to seed dormancy breaking treatments in rice species (Oryza L.). Seed Science and Technology 26:675-689.

Rao NK, Hanson J, Dulloo ME, Ghosh K, Nowel D, Larinde M. 2006. Manual of seed handling in genebanks. Handbooks for Genebanks No. 8. Bioversity International, Rome, Italy. Available in English (1.5 MB), Spanish (1.4 MB) and French (1.9 MB).

Reed BM, Engelmann F, Dulloo ME, Engels JMM. 2004. Technical guidelines for the management of field and in vitro germplasm collections. Handbook for Genebanks No. 7. IPGRI, Rome, Italy. Available here.

Sackville-Hamilton NRS, Chorlton KH. 1997. Regeneration of accessions in seed collections: a decision guide. Handbook for Genebanks No. 5. IPGRI, Rome, Italy. Available here.

Tateoka T. 1962a. Taxonomic studies of Oryza I. O. latifolia complex. Bot. Mag. Tokyo 75:418-427.

Tateoka T. 1962b. Taxonomic studies of Oryza II. Several species complexes. Bot. Mag. Tokyo 75:455-461.

Tateoka T. 1963. Taxonomic studies of Oryza III. Key to the species and their enumeration. Bot. Mag. Tokyo 76:166-173.

van Soest LJM.1990. Plant Genetic Resources: Safe for the future in genebanks. Impact of Science on Society 158:107-120.

Vaughan DA. 1989. The genus Oryza L. Current status of taxonomy. IRRI Research Paper Series 138, Manila, Philippines.

Vaughan DA, Sitch LA. 1991. Gene flow from the jungle to farmers. Bioscience Vol. 41(1):22-28.

Vaughan DA. 1992. The wild relatives of rice: A genetic resources handbook. IRRI, Los Baños, Philippines.

Vaughan DA, Chang TT. 1992. In situ conservation of rice genetic resources. Economic Botany 46(4):368-383.

Vaughan DA, Morishima H, Kadowaki K. 2003. Diversity in the Oryza genus. Current Opinion 6:139-146.

Characterization

Characterization